Fragile with care

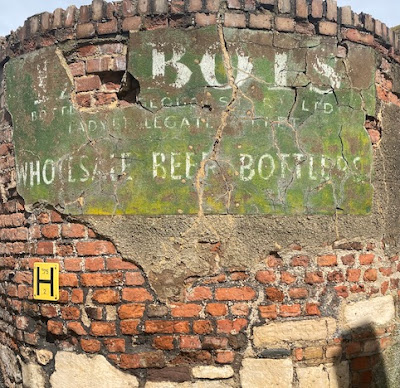

Back in 2008 I posted a picture of this ghost sign in Gloucester. I used the picture as a jumping-off point for a discussion of how such old signs accumulate meaning and significance. They represent the kind of craft that takes pains – with the choice of the letterforms, the way they are arranged, and the care with which the sign-writer painted them. They tell or remind us of long-forgotten industries. And in this case they summon up the way that beer might have been enjoyed, reminding us of the variety of different local brews that are no more. Signs like this, I thought then and still think, are worth taking notice of because they are triggers of memory, the sort of memory that tells us where we came from.

So whenever I’m in Ladybellegate Street in Gloucester, I remember to have a look at this sign, to help me summon up such memories, and to reassure myself that it’s still there. A couple of weeks ago it was still there, but in the 15 years since I took my original photograph, it has become more decayed and frayed around the edges, and looks as if there’s is risk of more of it parting company with the wall. That’s the sign as it was the other week in my photograph above; if you want to see the 2008 version and what I wrote about it back then, it is here. Both images are for me a reminder of something else: not only that these signs are fragile, but that their very fragility – the indistinctness of some of the letters and the way in which bits of plaster and paint have disappeared, is part of how we see them. The roughened surface and fragmentary text not only is more authentic than a repainted sign but looks the part too.

One day, the Talbot’s sign will be gone, like hundreds of others. Someone may choose to repaint it, as people have done with other ghost signs, and a repainted sign has some value. But much better in my view is the decayed original, still hanging on to the bricks that support it – hanging on, one hopes for another few years. Pay it homage, while it’s still there.

Wednesday, June 28, 2023

Tuesday, June 20, 2023

Tetbury, Gloucestershire

Continuity and change

If there’s one building in the Cotswold town of Tetbury that is impossible to miss, it’s the Market House, all seven bays of it, with its upper walls of cream-washed stone, its rows of deliciously plump Tuscan columns, its large clocks, and its bell turret. It was originally built in 1655 as a market for wool and yarn, the main products of the Cotswold Hills in those days, as for centuries before. The building has changed somewhat over the years. It was enlarged in the 18th century and some of the building’s more ornamental features actually date from a remodelling in the early-19th century. The triangular pediments with their clock faces, the hipped roof, and the bell turret all date to 1816–17. At some stage the Market House also acquired the metal dolphins that are displayed on brackets all the way along each of the long walls. These creatures come from the town’s coat of arms and making a pleasant decorative feature that baffles some visitors.

So a building that looks as if it has been here, virtually unchanged, for about 370 years has actually been altered as needs and fashions have changed, reflecting different needs and the wish to make the structure more up to date, or more prestigious. Over the years and at different times it has housed council meetings, law courts, a lock-up for criminals, markets of various kinds, and the town’s fire engine. And its life goes on. Goods are still sold in the sheltered area behind the columns – when I took this photograph, it was rugs and baskets being sold – and the building is hired out for markets, events, and parties. It’s still an important asset to the town, then, though perhaps not as crucial to its economy as in Tetbury’s 17th and 18th-century heyday. If the town today is as much about tourism and shopping as it is about agriculture, the Market Hall still provides a handsome focus for these activities.

If there’s one building in the Cotswold town of Tetbury that is impossible to miss, it’s the Market House, all seven bays of it, with its upper walls of cream-washed stone, its rows of deliciously plump Tuscan columns, its large clocks, and its bell turret. It was originally built in 1655 as a market for wool and yarn, the main products of the Cotswold Hills in those days, as for centuries before. The building has changed somewhat over the years. It was enlarged in the 18th century and some of the building’s more ornamental features actually date from a remodelling in the early-19th century. The triangular pediments with their clock faces, the hipped roof, and the bell turret all date to 1816–17. At some stage the Market House also acquired the metal dolphins that are displayed on brackets all the way along each of the long walls. These creatures come from the town’s coat of arms and making a pleasant decorative feature that baffles some visitors.

So a building that looks as if it has been here, virtually unchanged, for about 370 years has actually been altered as needs and fashions have changed, reflecting different needs and the wish to make the structure more up to date, or more prestigious. Over the years and at different times it has housed council meetings, law courts, a lock-up for criminals, markets of various kinds, and the town’s fire engine. And its life goes on. Goods are still sold in the sheltered area behind the columns – when I took this photograph, it was rugs and baskets being sold – and the building is hired out for markets, events, and parties. It’s still an important asset to the town, then, though perhaps not as crucial to its economy as in Tetbury’s 17th and 18th-century heyday. If the town today is as much about tourism and shopping as it is about agriculture, the Market Hall still provides a handsome focus for these activities.

Tuesday, June 13, 2023

Long Buckby, Northamptonshire

Self-help

The Northamptonshire village of Long Buckby still bears evidence of its part in the Northamptonshire shoe-making trade (at least one small factory building is still visible). During the shoe business’s 19th-century heyday, the place was also a centre of radicalism and religious nonconformity – the Chartist movement was strong here and there were three chapels as well as an Anglican parish church. Long Buckby was also home to Northamptonshire’s first cooperative society, which started in 1858. Part of its 1910 shop survives on a corner in the middle of the village, marked by this handsome sign. The clock, the specially made lettering and the frame with its scrolled brackets and curved top, are now by far the best part of a building sporting replacement windows and modern signs advertising the current occupants.

Although the British cooperative movement began in the late-18th century, cooperatives really took off after 1844. This was when the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers established the key principles of their cooperative organization.* So Long Buckby’s Self-Assistance Industrial Society was one of many that were started in the 20 years after the one in Rochdale.

Cooperatives’ main business was usually buying and selling goods following fair trade principles and distributing the profits to the members of the organization. Cooperatives could also offer other services, from banking to housing schemes. The Long Bucky society was one of many such coops that also operated a cinema, showing films to people who, in the days before mass car ownership, found it difficult to travel to a larger town with a purpose-built cinema. Although the showing of movies stopped there long ago, and the building that was once a shop and cinema now houses a gym, there is still a coop in the village operating on similar principles. The sign at the corner is a lasting reminder that such enterprises have a long history. It shows too that though we may be better now at many things than we were in 1910, our sign provision is often far less good than it used to be.

- - - - -

* For more about the Rochdale Pioneers, follow this link.

The Northamptonshire village of Long Buckby still bears evidence of its part in the Northamptonshire shoe-making trade (at least one small factory building is still visible). During the shoe business’s 19th-century heyday, the place was also a centre of radicalism and religious nonconformity – the Chartist movement was strong here and there were three chapels as well as an Anglican parish church. Long Buckby was also home to Northamptonshire’s first cooperative society, which started in 1858. Part of its 1910 shop survives on a corner in the middle of the village, marked by this handsome sign. The clock, the specially made lettering and the frame with its scrolled brackets and curved top, are now by far the best part of a building sporting replacement windows and modern signs advertising the current occupants.

Although the British cooperative movement began in the late-18th century, cooperatives really took off after 1844. This was when the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers established the key principles of their cooperative organization.* So Long Buckby’s Self-Assistance Industrial Society was one of many that were started in the 20 years after the one in Rochdale.

Cooperatives’ main business was usually buying and selling goods following fair trade principles and distributing the profits to the members of the organization. Cooperatives could also offer other services, from banking to housing schemes. The Long Bucky society was one of many such coops that also operated a cinema, showing films to people who, in the days before mass car ownership, found it difficult to travel to a larger town with a purpose-built cinema. Although the showing of movies stopped there long ago, and the building that was once a shop and cinema now houses a gym, there is still a coop in the village operating on similar principles. The sign at the corner is a lasting reminder that such enterprises have a long history. It shows too that though we may be better now at many things than we were in 1910, our sign provision is often far less good than it used to be.

- - - - -

* For more about the Rochdale Pioneers, follow this link.

Saturday, June 10, 2023

Faringdon, Berkshire*

A long view

They called it ‘Lord Berners’ monstrous erection’; they called it ‘the last folly’. But Lord Berners’ Folly will do, in memory of the versatile peer who was a modestly successful composer of modernist music and the occasional comic song, an able memoirist, and a rich eccentric of the old school who would entertain his friends by such exploits as dying his doves in brought colours and inviting Lady Betjeman and her horse to tea inside his house.

On his estate lies a hill, wooded at the top, which had been the site of fortifications – of King Alfred the Great, later of Queen Matilda – centuries ago. When the local council got permission to fell the trees for timber, Berners stepped in, bought the land, and saved the trees. He then employed the architect Gerald Wellesley to build this folly tower on the top of the hill. The story goes that the patron specified that the folly should be in the Gothic style but Wellesley, who disliked Gothic, made it Classical, until Berners discovered what he’d done and insisted on a Gothic lantern at the top. In truth the plain brick walls and arched windows are not very classical, and the octagonal lantern that capped the tower doesn’t look all that Gothic either – its pinnacles are plain, unlike the crocketed adornments of a latter-day Boston Stump. The folly is its own thing, a tall rather plain tower with a viewing room from which his lordship could admire the surrounding countryside; the vista stretches for many miles.

Apparently the locals weren’t too keen when they discovered that Lord Berners was building a tower on the hill above their town. But they got used to the idea and now people seem to embrace it, admiring the architecture and taking the chance to enjoy the view on the regular occasions when the folly is open. Eccentrics and good views: two things that the English traditionally like…and still, in most cases, have time for.

- - - - -

*Or Oxfordshire, in modern parlance

Monday, June 5, 2023

Painswick, Gloucestershire

Welcome to the Eagle House

The Eagle House is a building on the edge of Painswick Rococo Garden and is one of those that the garden’s restorers had to reconstruct in part. The building is in two storeys – a lower section with a large Gothic archway and an upper level which is a small hexagonal pavilion, generously supplied with pointed Gothic windows that give views over the gardens. The good views from this cliff-top, eyrie-like structure form one reason for the building’s name; the other reason is that an eagle did live in it for a while, during the 19th century.

A drawing by Thomas Robins from the 1750s gave the restorers the best clues as to how to rebuild the upper storey, which had perished some time after the eagle’s period in residence. The present design, with the hexagon peeping up from above the row of stone battlements that top the arch below, follows Robins’s drawing closely. Archaeology revealed not only the foundations of the upper storey but also some fragments of its structure, including pieces of plaster in the pink colour used for the finish. The Gothic windows, the unusual hexagonal shape, the lightness of the upper section, and the pink colour are all features associated with the Rococo manner that give the garden its current name.

Another interesting aspect of the building is that it is possible to see the upper storey as one enters the garden, without realising that there is also a lower portion, which is revealed only when the visitor descends via a looping path. This element of surprise in the layout of a garden was something else Rococo designers and garden-owners of the 18th and 19th centuries relished. The novelist Thomas Love Peacock (1785–1866) satirised this preoccupation with surprise in his novel Headlong Hall, when Squire Headlong and two of his guests discuss landscape gardening:

‘Allow me,’ said Mr Gall. ‘I distinguish the picturesque and the beautiful and add to them, in the laying out of grounds, a third and distinct character, which I call unexpectedness.’

‘Pray, sir,’ said Mr Milestone, ‘by what name do you distinguish this character, when a person walks round the grounds for a second time?’

Mr Gall bit his lips, and inwardly vowed to revenge himself on Miletsone, by cutting up his next publication.

Poor Mr Gall, being taken to task for, admittedly, being rather pompous about something light-hearted. For that, to my mind, is the point of gardens like this. They are a world away from the philosophical gardens of the period, in which buildings are freighted with moral or political meanings – Stowe is a wonderful example of this kind of outlook. The Rococo Garden seems to be above all about pleasure and delight, and is no worse for that.

How lucky were the 18th-century owners of the garden to be able to sit in this hexagonal pavilion and look out over their creation. How fortunate are those who, like me, paid up at the entrance and looked out through these windows. Or browsed through the selection of second-hand books now stocked on shelves beneath the windows. Gardens, architecture, literature: how much better can it get?

Friday, June 2, 2023

Painswick, Gloucestershire

Cotswold Rococo

In 1984 Lord and Lady Dickinson, owners of the Painswick House estate, decided to restore the 18th-century garden in a hidden valley behind the house. The area had been neglected for years, the garden abandoned, and part of the site eventually made over to a commercial conifer plantation. Restoration meant clearing decades of rubbish, working out what remained of the original structures, no doubt uprooting any remaining conifers, and repairing (and sometimes reconstructing) garden buildings. This was a huge undertaking and would have been impossible were it not for a painting (and drawings) of the garden in its mid-18th century prime by local artist Thomas Robins.

What has emerged over the decades since 1984 is a garden in the Rococo taste, with walks, pools, vistas, a wooded glade, a kitchen garden, a vineyard, planting with species available in the 18th century, and numerous pavilions and other architectural structures. Some of the buildings were restored to something close to their 18th-century state, some were rebuilt completely following the Robins pictures, for some a compromise was achieved, with certain structures restored to a state similar to the way they were in the 19th century.

One of the most striking buildings is the Red House, which sits at one end of the garden, at a point where formal beds and clipped hedges give way to a riot of natural vegetation and wild flowers. It is not only a belter of an eyectacher, but also exemplifies some of the key features of the Rococo. These are: asymmetry, the interesting use of colour, scrolls and curlicues, rich ornamentation, playfulness, and eclecticism of style (the building owes much to Gothic, but the roofline of the right-hand room takes a concave form derived from Chinese sources). This building of the 1740s adopts a fancy and fanciful kind of Gothic detailing with an ogee (double-curved) gable, deep cusped ogee canopies to windows and doorway, large finials, upside-down trefoil-shaped openings, exaggerated buttress-like stone uprights with concave-slopes to the gables. This is similar to the kind of Gothic used by Horace Walpole at his Twickenham house, Strawberry Hill, at around the same time as the Rococo Garden was begin constructed.

A further Rococo feature of the Red House is the way in which the two wings are set at a slight angle, another piece of asymmetry that seems odd until one realises that the two rooms face two different paths that converge here, one leading along the edge of the garden, the other heading towards its centre. So whichever path you take to approach the Red House, one of its wings acts as a focal point: the building is ingeniously integrated into the plan of the garden.

Painswick Rococo Garden, as it’s now known, is a unique example of a Rococo garden in England. To those interested in architecture, it offers half a dozen small delights like the Red House. For those whose main interest is the horticultural side of things, the place is stunning in the snowdrop season (it has one of the best collections of snowdrops anywhere), delightful in the late spring when we visited (though we were a little late to see the bluebells at their best), and its wooded sections must be beautiful in autumn too. But the point is not to separate buildings and plants, but to appreciate how well they are integrated. The effect is a triumph of 18th-century design and 20th-century restoration.

In 1984 Lord and Lady Dickinson, owners of the Painswick House estate, decided to restore the 18th-century garden in a hidden valley behind the house. The area had been neglected for years, the garden abandoned, and part of the site eventually made over to a commercial conifer plantation. Restoration meant clearing decades of rubbish, working out what remained of the original structures, no doubt uprooting any remaining conifers, and repairing (and sometimes reconstructing) garden buildings. This was a huge undertaking and would have been impossible were it not for a painting (and drawings) of the garden in its mid-18th century prime by local artist Thomas Robins.

What has emerged over the decades since 1984 is a garden in the Rococo taste, with walks, pools, vistas, a wooded glade, a kitchen garden, a vineyard, planting with species available in the 18th century, and numerous pavilions and other architectural structures. Some of the buildings were restored to something close to their 18th-century state, some were rebuilt completely following the Robins pictures, for some a compromise was achieved, with certain structures restored to a state similar to the way they were in the 19th century.

One of the most striking buildings is the Red House, which sits at one end of the garden, at a point where formal beds and clipped hedges give way to a riot of natural vegetation and wild flowers. It is not only a belter of an eyectacher, but also exemplifies some of the key features of the Rococo. These are: asymmetry, the interesting use of colour, scrolls and curlicues, rich ornamentation, playfulness, and eclecticism of style (the building owes much to Gothic, but the roofline of the right-hand room takes a concave form derived from Chinese sources). This building of the 1740s adopts a fancy and fanciful kind of Gothic detailing with an ogee (double-curved) gable, deep cusped ogee canopies to windows and doorway, large finials, upside-down trefoil-shaped openings, exaggerated buttress-like stone uprights with concave-slopes to the gables. This is similar to the kind of Gothic used by Horace Walpole at his Twickenham house, Strawberry Hill, at around the same time as the Rococo Garden was begin constructed.

A further Rococo feature of the Red House is the way in which the two wings are set at a slight angle, another piece of asymmetry that seems odd until one realises that the two rooms face two different paths that converge here, one leading along the edge of the garden, the other heading towards its centre. So whichever path you take to approach the Red House, one of its wings acts as a focal point: the building is ingeniously integrated into the plan of the garden.

Painswick Rococo Garden, as it’s now known, is a unique example of a Rococo garden in England. To those interested in architecture, it offers half a dozen small delights like the Red House. For those whose main interest is the horticultural side of things, the place is stunning in the snowdrop season (it has one of the best collections of snowdrops anywhere), delightful in the late spring when we visited (though we were a little late to see the bluebells at their best), and its wooded sections must be beautiful in autumn too. But the point is not to separate buildings and plants, but to appreciate how well they are integrated. The effect is a triumph of 18th-century design and 20th-century restoration.