A glimpse of the heavens

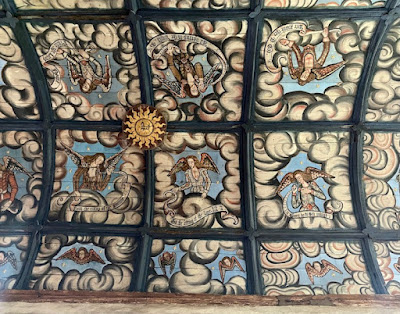

En route across Somerset, I decided to stop at Muchelney, where I’d not been for years. I planned to revisit the medieval abbey, but was also drawn to the adjacent but quite separate parish church of Saints Peter and Paul. The church is late-15th century, like so many in Somerset, but what I most wanted to see again was a later embellishment, the 17th-century ribbed and boarded ceiling of the nave, with its wonderful painted panels of angels looking down from the clouds.

I have not seen anything else quite like this ceiling (the angels in the church ceiling at Bromfield, Shropshire, come closest, but I’d say they are slightly later and in a different style). Each panel at Mucheleny is edged with clouds, which swirl like cotton wool or whipped cream, but are edged in darker shades. English clouds, of course, often combine the hopeful white with the threatening grey, but not quite in the stylized way of these ceiling paintings, and the stylization is part of their charm, which is easier to appreciate if you click on the image to enlarge it.

I find the angels charming too. They stand behind the clouds, and look down through the gaps between them; behind each figure is blue sky dotted with tiny stars, suggesting the angels are in a heavenly realm far above the clouds, farther still from us earthbound humans. They’re a far cry from medieval angels of any kind; neither are they like chaste Victorian angels. They have boldly painted faces, shoulder-length hair, and perky wings and they are are clothed in something like Elizabethan or Jacobean dresses, but in what Pevsner describes as ‘extreme décolletage’. The contours of their breasts vary – some look markedly rounded and suggest the human female form, some are less so. Those who feel compelled to explain such things suggest that their revealing costumes suggest their innocence, which sounds like a modern explainer trying very hard to justify what they see as inappropriate. Authorities such as Pevsner and the people who wrote the listing description for the church, avoid explanation altogether. I’d say anything that purports to be an explanation is at best informed guesswork.

The messages spoken by the angels, written on scrolls that they hold, are clear enough. ‘Good will towards men’, ‘Wee praise thee O God’, ‘All nations in the world…praise the Lords Name’, and so on. The sun, a golden roundel set at the intersection of four panels, looks on approvingly. From the floor below, I look up with similar approval at the whole ceiling – with more than approval indeed and with pleasure at another example of how the art of English churches can be colourful, unexpected, and full of joy.

Thursday, August 31, 2023

Thursday, August 24, 2023

Stanton, Gloucestershire

Sheepdogs, or, Odd things in churches (16)

I can’t remember when I first went inside the church of St Michael and All Angels, Stanton, in the north Cotswolds, but I think I already knew the story behind the bench-end in my photograph. Perhaps I knew the story from the Gloucestershire volume of Arthur Mee’s series, ‘The King’s England’, probably the only book that my parents had that would have held such a historical tidbit: ‘It may be that when Wesley preached in this place there listened to him shepherds from the hills who would tie their dogs to the ends of the benches, which still have the marks of the chafing of the chains which held the dogs.’ Such marks can certainly be seen on the bench end in my picture, perhaps from the chains themselves or from a metal ring to which chains were attached.

Can this be true? It’s certainly plausible. For centuries, Cotswold farms were the sheep farms par excellence of England. For years I’ve lived in this part of the country and there are still plenty of sheep farmed around here. Shepherds might these days ride around on quad bikes or in 4 x 4s, and wherever they go their dogs go with them. In church, in the 18th century or earlier, one can imagine the chained dogs excited on their weekly meeting with the neighbours pulling on their chains and chafing at the woodwork before settling down quietly by the time the service began. We’re often told that Cotswold churches (like many in Suffolk and other areas) were built from the proceeds of the wool trade. It’s good to be reminded that none of that money could have been made without the people who raised the sheep – and the animals that rounded them up.

Tuesday, August 22, 2023

Withypool, Somerset

Pump heaven

I’m not quite sure why I like old petrol pumps and garages. As far as the pumps are concerned it’s partly, I think, nostalgia and partly design – the lovely advertising globes on the tops of the pumps and the lines of the pumps themselves, which altered from one decade to the next as fashions changed. I think these Beckmeter pumps in the village of Withypool are probably from the 1960s. The shape, all straight lines, and the frames of chrome around the dials certainly look as if they’re from that decade, and online sources suggest I’m right. These pumps would be at home in front of a flat-roofed building with a large area of plate glass on the front. By the 1970s, similar-shaped pumps were still fashionable, but they increasingly had digital displays – the ones in which the digits were set on cylinders that rotated, bringing the next number gradually to the front. The star system for rating petrol (the pump in the foreground has two stars) came in during 1967, so that fits too, although the panel at the top where the stars are located was probably something that the garage owner or petrol company could change with ease. The shell-shaped globes, of course, are throwbacks to an earlier era. Shell globes in a similar design go back to 1929; the details of the design evolved, and the Shell globes were fitted to all kinds of different pumps.

Beckmeter pumps were ubiquitous back in the sixties and seventies. The company was founded as a general engineering concern in the Victorian era, and they gradually came to specialise in water meters and vales. When cars became increasingly common, in the interwar period, Beck’s adapted their water meter designs for use with petrol and soon manufacturing petrol pumps was a major part of their business. Of course these pumps lasted for years, and it was possible in, say, the 1980s, to find 30- or 40-year old pumps dispensing fuel. Hence their survival at filling stations like this one, long closed, in a remote Exmoor village.

I find the sight of them still lined up at a stone-built filling station, its woodwork painted to match the red of the Shell colours, very satisfying. Even more satisfying is that there’s an even older (1940s or 1950s) Avery-Hardoll pump (photo below) just across the road. Again, this one, now missing its globe, appears typical of its time – the tapering shape of the pump body and the script-style lettering of the Avery-Hardoll name look the part and the period.

Now there’s as much of a demand for coffee as for petrol, the forecourt with the Beckmeter pumps at Withypool has been taken over by a table, and refreshment is available from the building next door. So there’s a good reason for cyclists and walkers to stop here as well as motorists, and a good reason, I’d argue, for all of them to admire these examples of historical engineering and design.

I’m not quite sure why I like old petrol pumps and garages. As far as the pumps are concerned it’s partly, I think, nostalgia and partly design – the lovely advertising globes on the tops of the pumps and the lines of the pumps themselves, which altered from one decade to the next as fashions changed. I think these Beckmeter pumps in the village of Withypool are probably from the 1960s. The shape, all straight lines, and the frames of chrome around the dials certainly look as if they’re from that decade, and online sources suggest I’m right. These pumps would be at home in front of a flat-roofed building with a large area of plate glass on the front. By the 1970s, similar-shaped pumps were still fashionable, but they increasingly had digital displays – the ones in which the digits were set on cylinders that rotated, bringing the next number gradually to the front. The star system for rating petrol (the pump in the foreground has two stars) came in during 1967, so that fits too, although the panel at the top where the stars are located was probably something that the garage owner or petrol company could change with ease. The shell-shaped globes, of course, are throwbacks to an earlier era. Shell globes in a similar design go back to 1929; the details of the design evolved, and the Shell globes were fitted to all kinds of different pumps.

Beckmeter pumps were ubiquitous back in the sixties and seventies. The company was founded as a general engineering concern in the Victorian era, and they gradually came to specialise in water meters and vales. When cars became increasingly common, in the interwar period, Beck’s adapted their water meter designs for use with petrol and soon manufacturing petrol pumps was a major part of their business. Of course these pumps lasted for years, and it was possible in, say, the 1980s, to find 30- or 40-year old pumps dispensing fuel. Hence their survival at filling stations like this one, long closed, in a remote Exmoor village.

I find the sight of them still lined up at a stone-built filling station, its woodwork painted to match the red of the Shell colours, very satisfying. Even more satisfying is that there’s an even older (1940s or 1950s) Avery-Hardoll pump (photo below) just across the road. Again, this one, now missing its globe, appears typical of its time – the tapering shape of the pump body and the script-style lettering of the Avery-Hardoll name look the part and the period.

Now there’s as much of a demand for coffee as for petrol, the forecourt with the Beckmeter pumps at Withypool has been taken over by a table, and refreshment is available from the building next door. So there’s a good reason for cyclists and walkers to stop here as well as motorists, and a good reason, I’d argue, for all of them to admire these examples of historical engineering and design.

Thursday, August 17, 2023

Devizes, Wiltshire

Landmark base

I’ve passed this building a number of times when driving into or through Devizes in Wiltshire – one can’t fail to notice it, but it’s one of those buildings that is easy to pass by because you’re on the way to somewhere else. Coming out of the town the other week, I resolved to find a place to stop, have a closer look, and take a photograph. I knew little about it except that it was a former army barracks and that it was built in the late-19th century.

Its original role dates back to a series of reforms of the British army undertaken in the 1860s and 70s by the Liberal Prime Minister W. E. Gladstone and his Secretary of State for War, Edward Cardwell. The reforms involved abolishing the practice of buying commissions in the army, changing the way the War Office worked, and setting up reserve forces based in Britain. The barracks in Devizes were home to one of these forces, and was named after the illustrious cavalry commander John Le Marchant. For a long period the building was home to the Wiltshire Regiment, although during World War II it was used as a prisoner of war camp.

The castle-like architecture clearly signals the barracks’ military function – the part in my photograph is clearly built to resemble a castle keep, although longer blocks running to the left and behind this ‘keep’ are less military looking. The long blocks are the barracks themselves – the accommodation for the soldiers. The keep building contained a guard room, detention cells, and storage areas and armouries. The keep is a highly symbolic part of the complex. It is gratifying that it has survived the closure of the barracks and the eventual conversion of the site to housing – a structure that both embodies the past and reminds people today of the old phrase about an Englishman’s home being his castle.

I’ve passed this building a number of times when driving into or through Devizes in Wiltshire – one can’t fail to notice it, but it’s one of those buildings that is easy to pass by because you’re on the way to somewhere else. Coming out of the town the other week, I resolved to find a place to stop, have a closer look, and take a photograph. I knew little about it except that it was a former army barracks and that it was built in the late-19th century.

Its original role dates back to a series of reforms of the British army undertaken in the 1860s and 70s by the Liberal Prime Minister W. E. Gladstone and his Secretary of State for War, Edward Cardwell. The reforms involved abolishing the practice of buying commissions in the army, changing the way the War Office worked, and setting up reserve forces based in Britain. The barracks in Devizes were home to one of these forces, and was named after the illustrious cavalry commander John Le Marchant. For a long period the building was home to the Wiltshire Regiment, although during World War II it was used as a prisoner of war camp.

The castle-like architecture clearly signals the barracks’ military function – the part in my photograph is clearly built to resemble a castle keep, although longer blocks running to the left and behind this ‘keep’ are less military looking. The long blocks are the barracks themselves – the accommodation for the soldiers. The keep building contained a guard room, detention cells, and storage areas and armouries. The keep is a highly symbolic part of the complex. It is gratifying that it has survived the closure of the barracks and the eventual conversion of the site to housing – a structure that both embodies the past and reminds people today of the old phrase about an Englishman’s home being his castle.

Sunday, August 13, 2023

Northampton

Walking past the entrance to the Royal and Derngate Theatre in Northampton, I focused rapidly on the large building beyond and its tall, multi-windowed brick frontage. I’m fond of Victorian buildings of polychrome brick, the jazzier examples of which often date from the 1860s or 1870s. What was this one, I wondered, with its attractive mix of red, buff, and blue brickwork? Following the line of the vertical buff bands upwards, I noticed quickly how they end, above the top windows, in pointed arches, each pair united under a larger rounded arch. The dark triangular areas beneath each pointed arch seem to contain wooden louvres, for ventilation.

In the kite-shaped space between the pairs of pointed arches is an area of buff masonry, and I could just make out a carved date, 1876, in one such space and some initials, P & S, in some of the others. The P, at least, is a clue, since it turns out that this building belonged to Northampton’s biggest brewer, Phipps. They produced beer in nearby Bridge Street and the building in my photograph was their warehouse. What a scene of bustle this must have been in the late-Victorian period, with horse-drawn drays setting off from here to pubs not just in Northampton but also in towns and villages round about. In the 20th century, the local Cooperative Society put up a large building in this street, and nearby there was also a handsome Victorian hotel, to add to the hubbub. There is still much coming and going in the street, including people seeking out the Museum and Art Gallery, on the opposite side of the road from the Phipps building. The hustle and bustle continues.

Tuesday, August 8, 2023

Northampton

Lasting well

My time in Northampton the other day was spent in the centre of the town, and so I did not take in the remains of the town’s most famous industry, shoe-making. But on one street corner I came across a building that did relate to the business of shoes and leather goods. Being an enthusiast for architectural carving, I lingered by this doorway, fascinated by its combination of bulls’ heads, elegant women, fishes, stylized trees, and meticulously carved lettering. What on earth, I wondered, did it all mean?

A little research told me that Malcolm Inglis and Co were leather factors, dealers in the material that was crucial for the town’s shoe manufacturers. What more appropriate business to be based in the centre of Northampton? The fact that Malcolm Inglis and Co could set themselves up so impressively – their building is mainly of stone, with a little brickwork here and there – suggests that they were doing very well here. The structure was their showroom and offices, so the unashamedly showy entrance, strategically placed on the corner of Fish Street and The Ridings, both looks good and makes sense.

A Glasgow architect, Alexander Anderson, supplied the design in 1900. The sculptor of the magnificent portal was Abraham Broadbent, a Yorkshireman from a family of stone masons. He won a studentship at the South London Technical School of Art in 1895. Once he was in London, it did not take him long to become a prominent architectural sculptor. Among other work, he produced sculpture for the facade of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. In his carving for Malcolm Inglis, he shows the influence of the then-fashionable Art Nouveau style – the stylized trees and female figures are very Art Nouveau, while his clear lettering is more sober (and more legible) than Art Nouveau’s more elaborate examples. The result is a good bit of street-frontage art, of which Glasgow and Northampton (and indeed Yorkshire) should be proud.

My time in Northampton the other day was spent in the centre of the town, and so I did not take in the remains of the town’s most famous industry, shoe-making. But on one street corner I came across a building that did relate to the business of shoes and leather goods. Being an enthusiast for architectural carving, I lingered by this doorway, fascinated by its combination of bulls’ heads, elegant women, fishes, stylized trees, and meticulously carved lettering. What on earth, I wondered, did it all mean?

A little research told me that Malcolm Inglis and Co were leather factors, dealers in the material that was crucial for the town’s shoe manufacturers. What more appropriate business to be based in the centre of Northampton? The fact that Malcolm Inglis and Co could set themselves up so impressively – their building is mainly of stone, with a little brickwork here and there – suggests that they were doing very well here. The structure was their showroom and offices, so the unashamedly showy entrance, strategically placed on the corner of Fish Street and The Ridings, both looks good and makes sense.

A Glasgow architect, Alexander Anderson, supplied the design in 1900. The sculptor of the magnificent portal was Abraham Broadbent, a Yorkshireman from a family of stone masons. He won a studentship at the South London Technical School of Art in 1895. Once he was in London, it did not take him long to become a prominent architectural sculptor. Among other work, he produced sculpture for the facade of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. In his carving for Malcolm Inglis, he shows the influence of the then-fashionable Art Nouveau style – the stylized trees and female figures are very Art Nouveau, while his clear lettering is more sober (and more legible) than Art Nouveau’s more elaborate examples. The result is a good bit of street-frontage art, of which Glasgow and Northampton (and indeed Yorkshire) should be proud.

Tuesday, August 1, 2023

Somewhere in the Cotswolds

Corrugated surprise

There’s a way of thinking about architecture that puts building materials in a hierarchy of prestige and value. At the top of the list is stone, the material of cathedrals and palaces, a substance that requires great skill to work, is long lasting, and can be carved to produce the kind of ornament that sets off a grand facade or an imposing interior. Next in the order comes brick, also long-lasting, but mostly mass-produced; there are some major buildings in brick, but for those who think in hierarchies, brick has something of the everyday about it. The descending order continues with wood, and thence on downwards. The position of concrete in this league table is more debatable than most. But one thing that many people have agreed on is that buildings of corrugated iron come somewhere near the bottom of the heap. And of course I am here to tell you that this whole notion – the hierarchy itself, and the dissing of corrugated iron, is all so much nonsense.

There was a time when no one thought of corrugated iron buildings as architecture at all. The material is missing from most histories of architecture and when people consider it, it’s in terms of utilitarian structures like sheds, barns, and aircraft hangars – ‘tin sheds’ was the old deprecating phrase.. These days, however, corrugated iron is taken much more seriously. Its history has been researched, there are several books on the corrugated iron architecture,* there’s even a Corrugated Iron Appreciation group on Facebook. People who worship in a ‘tin church’ or live in a corrugated iron house can be proud of their buildings, and rightly so.

Recently I came across a small group of corrugated iron houses in the Cotswolds, little more than ten miles from where I live. I’d no idea they were there, and to preserve the privacy of their occupants I’m not revealing their precise location. I show one of them in my picture. It appears, to me, very attractive, cosy-looking,† framed by its well kept garden and screened from the nearby road by trees. The green paintwork helps it blend in – corrugated iron buildings are often green, a colour that works well, although I’ve also seen them painted almost every colour of the rainbow. The sun casts strong shadows and brings out the pleasing texture of ridges, although it was in the ‘wrong’ direction when I saw these houses to enable a photograph that really does them justice.

Back in the 19th and early-20th centuries, you could buy a flat-pack corrugated iron house from a manufacturer and have it shipped to your site. You needed to prepare a good base, lay on services like water and plumbing, bolt the frame together, screw on the sheets of wriggly tin, and add interior cladding, perhaps with insulating material in the gap between the inner and outer ‘skins’. Perhaps these houses started life in that way. Or maybe, since I’ve read about an old hospital somewhere near where these buildings are, they started life as part of that – corrugated iron hospitals were produced and constructed in a similar way, and were often used as tuberculosis hospitals in remote rural areas. However they started life, these green-painted houses still seem to be doing good service and have no doubt lasted longer than their original builders could have predicted. And that’s surely green in another important sense.

- - - - -

* For example: Simon Holloway and Adam Mornement, Corrugated Iron: Building on the Frontier (W. W. Norton, 2008) and Nick Thomson, Corrugated Iron Buildings (Shire Books, 2011)

† Doubters ask if corrugated iron buildings aren’t very cold in the winter, and wonder whether rain on the roof makes too much noise. Some say that good insulation goes a long way to solving both problems.