Local colour

How could it be? I’d been to Suffolk several times and looked around so many of its towns – Aldeburgh, Southwold, Lavenham, Sudbury, Stowmarket… How had I not been to Hadleigh? This time, the Resident Wise Woman and I resolved to correct this omission, and quite early one December morning two weeks before Christmas, we arrived in Hadleigh, wandered around, and were very impressed. There is so much for the building-fancier to see, and so much of it is good.

It wasn’t long before we found the churchyard, and it was not only the church that caught our eye. Along one side of God’s acre is the conglomeration of brickwork, timber-framing and ochre-coloured plaster in my photograph. It’s now known as the Guildhall-Town Hall complex and the rooms inside are available to the local community for various uses. The earliest part is the timber-framed section in the middle, which was constructed in the mid-15th century. This was built as a market hall, with shops below and other rooms on the jettied storeys above. Behind this is the Guildhall, built as a wing projecting from the back of the market hall – a tiny portion of this is visible near the left-hand edge of my photograph.* The two-storey wings on either side of the timber-framed market hall are later.

The complex has had a variety of uses since the Middle Ages. It was the administrative centre when Hadleigh was a borough in the 17th century; until 1834, part of the building was used as the parish workhouse; more than one school had been based here; part of the structure was once almshouses; and in the early-20th century it was partly used as a corset factory. There’s something admirable about a building that’s in part almost 600 years old and has been used in so many ways – and is still an asset to the town. It’s also admirable that it has fulfilled these uses while keeping much of its ancient beauty.

- - - - -

* Guildhalls were the headquarters of guilds, associations of tradesman or merchants, formed for various reasons including religious (for example, paying for prayers for the souls of the dead) and charitable (for example, providing for the surviving families of deceased members).

Thursday, December 28, 2023

Thursday, December 21, 2023

Huish Episcopi, Somerset

With my best wishes

Casting around for something seasonal to post, I found this picture in my files. I’ve actually posted it before, but so long ago that I doubt anyone reading this now will remember it from back then. It’s a stained glass window designed by Edward Burne-Jones and made in the workshop of William Morris and it shows the Nativity scene in the stable at Bethlehem. As well as being a prominent member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Burne-Jones was also a founder member of Morris’s firm and the window is one of many wonderful examples of their bringing together of art, craft and design.

The host of angels, crowding beneath the roof of the stable and into the foreground, focus their gaze on Mary and Jesus. Mary is recumbent, as she often is in ancient images of the scene, and so she and the child form a long centre band across the window, with angels above and below. On the left-hand side of the picture, the Magi wait to present their gifts. I like everything about this window, from the colours and the composition to the tenderness with which the mother holds her baby and the way in which the heads of the figures in the side panels lean in towards the holy family. I hope you like it too.

Have a happy Christmas and may the new year bring peace, not least to the part of the world where this scene took place.

- - - - -

Note You may be able to see a little more detail if you click on the photograph.

Saturday, December 16, 2023

Boxford, Suffolk

Sign of the times

It’s 1839 and you are building a new house (or perhaps refronting an old one) in the middle of Boxford, Suffolk. Queen Victoria came to throne two years ago and was popular at the beginning of her reign. So you decide to name the house after the young monarch: Victoria Cottage. Perhaps the building was completed at the beginning of the year, because as 1839 went on, Victoria’s popularity was dealt a blow when she was implicated in spreading false rumours about one of her mother’s ladies-in-waiting. Or perhaps the house’s owner was staunchly patriotic. Who knows? Both the name, inscribed over the arches above the lower windows, and the date of construction, above the windows of the upper floor, remain. The inscriptions are certainly an individual touch and a far cry from the small house name signs or date stones more often seen on modest town houses.

The frontage is classically plain – the arches, round-topped windows, parapet, and Gothic glazing bars are all reminiscent of the late-Georgian period, but fashions were often slow to change in the provinces and, in style as in inscriptions, individual taste is often in play in domestic architecture. The bricks are the pale colour so often found in East Anglia and featuring also in the building in my previous post. Pale bricks, often called ‘whites’, but often pale yellow or cream in colour, are made with clay that contains more lime than usual, a feature of clays in many parts of eastern England. They can look very handsome, sometimes easy to mistake for stone when one is looking at a big country house from a distance, but here are unmistakably brick and none the worse for that.

Tuesday, December 12, 2023

Boxford, Suffolk

Preserve, re-use, re-use again

In Boxford primarily to look at the church, my eye of course was caught in addition by other things. This small building in the middle of the village made me scratch my head. What is it? The date, 1838, took my mind back to the era of village lock-ups, and this seems to have been the answer. Two stout wooden doors would have originally provided security for a two-celled mini-prison, where wrongdoers were kept, usually just for a short period before they were either released or taken to court. Drunks would be left until they were sober, two people who had got into a fight could be locked up and separated by a solid brick wall, those suspected of more serious misdemeanours would be locked up until they went before a justice or magistrate.

Lock-ups usually featured simple and functional architecture, but here the builders allowed themselves a couple of four-centred arches and a generous brick gable to make the structure look imposing.* The bricks are the pale ones seen widely in East Anglia. When no longer needed as a lock-up, the building was used to store the village fire engine (it would have been a small, hand-pumped device). Today it’s used simply as a shelter, a nice example of an antiquated building finding a new use that makes it worth preserving as something more than a mere eye-catcher – although it certainly fulfils that function too.

- - - - -

* Although we are a fair distance from the sort of chunk prison architecture that is sometimes seen; for an example, see this one here in Bewdley, Worcestershire.

Friday, December 8, 2023

Shrewton, Wiltshire

Earthy

Looking through my pictures the other day for something else, I found this picture that I took years ago and probably meant to blog. It’s the gate lodge to an adjacent manor house and stands proud and white near a road junction (near where the village lock-up is also to be found), a very effective architectural signpost, as it were, to the gate to the larger dwelling. It’s built of cob, a material consisting of earth, water, sand, and straw. Cob is associated most closely with Devon, Cornwall, and Norfolk, although it’s also found in Wiltshire (and in Buckinghamshire, where it’s known as wychert). The walls are likely to be quite thick (about 2 ft) and offer good heat insulation, but need a well maintained overhanging roof to keep them dry. This one has a hipped roof of thatch to do the job.

The Gothic windows suggest a late-18th century date, which is what is suggested in the official listing description of this building. The house looks substantial, and also has a modern extension, part of which is just visible in my photograph, so would provide accommodation for someone who worked for the owners of the manor house, together with their family. I’ve written blog posts about several lodges before,* including a number with thatched roofs, because these are often striking, ornamental buildings. I was glad to find this one again among my pictures, and looking at it has made me resolve to return to Shrewton one day – according to the revised Pevsner volume for Wiltshire, there’s a cob crinkle-crankle wall somewhere nearby, which I missed. When you visit a place once, there’s nearly always something else to see when you retiurn.

- - - - -

* For more, click the word ‘lodge’ in the list of topics in the right-hand column.

Looking through my pictures the other day for something else, I found this picture that I took years ago and probably meant to blog. It’s the gate lodge to an adjacent manor house and stands proud and white near a road junction (near where the village lock-up is also to be found), a very effective architectural signpost, as it were, to the gate to the larger dwelling. It’s built of cob, a material consisting of earth, water, sand, and straw. Cob is associated most closely with Devon, Cornwall, and Norfolk, although it’s also found in Wiltshire (and in Buckinghamshire, where it’s known as wychert). The walls are likely to be quite thick (about 2 ft) and offer good heat insulation, but need a well maintained overhanging roof to keep them dry. This one has a hipped roof of thatch to do the job.

The Gothic windows suggest a late-18th century date, which is what is suggested in the official listing description of this building. The house looks substantial, and also has a modern extension, part of which is just visible in my photograph, so would provide accommodation for someone who worked for the owners of the manor house, together with their family. I’ve written blog posts about several lodges before,* including a number with thatched roofs, because these are often striking, ornamental buildings. I was glad to find this one again among my pictures, and looking at it has made me resolve to return to Shrewton one day – according to the revised Pevsner volume for Wiltshire, there’s a cob crinkle-crankle wall somewhere nearby, which I missed. When you visit a place once, there’s nearly always something else to see when you retiurn.

- - - - -

* For more, click the word ‘lodge’ in the list of topics in the right-hand column.

Friday, December 1, 2023

Birlingham, Worcestershire

Recycling

Many English churches were built in the Victorian period. Lots of these served new parishes, created to serve a population that was growing faster than ever before. But some were replacements of older buildings, churches that had deteriorated structurally, or were too small for current needs, or just had the misfortune to have been built in a way that offended Victorian sensibilities. When this was the case, one cannot help but wonder what the original building was like, and whether it was really necessary to knock it down.

Sometimes there are clues in old watercolours or engravings, or written accounts by antiquarians. Occasionally, there are architectural fragments of the old building sill to be seen. This is the case in the village of Birlingham, where the Norman chancel arch of the old church (rebuilt in 1871–72 by Benjamin Ferrey with the exception of the tower) was reused as the gateway to the churchyard. So what could have become a heap of rubble has been turned into a rather grand ceremonial entrance. It does, of course, contain much 19th-century workmanship (‘much renewed by Ferrey’ is Pevsner’s comment), but it gives us an idea of the old arch, and forms a pleasant focal point (not to mention a talking-point) in the centre of the village. Here’s to recycling.

Monday, November 20, 2023

Launceston, Cornwall

Music for a long while

On several occasions when exploring English buildings I’ve come across ancient carvings of musicians. Blog posts from years ago have featured a bagpiper in Cornwall and a player of a medieval woodwind instrument called a rackett in Gloucestershire. Some years ago in Cornwall again, visiting St Mary Magdalene’s church at Launceston, I found a whole band of musicians carved into the stone of the outside walls.

Launceston church, like many in Cornwall, is built of local granite, one of the hardest of all stones and difficult, for that reason, to carve. Yet the stonemasons of Launceston, rebuilding the church in around 1511, were determined to decorate it as ornately as any other. In fact I can’t think of another English parish church so richly encrusted with carvings – Pevsner says that the building is decorated with ‘barbarous profuseness’. I’d not use such loaded language. I find the carvings fascinating, and I’m awed by the masons who could carve this intractable material, even though the granite’s hard surface means that they could not carve with the depth or detail that they might have achieved in, for example, limestone.

Amongst the decorative profusion – leaves, ferns, roses, thistles, pomegranates, heraldry – are several relief carvings showing musicians (in the upper left part of my photograph: click it for an enlargement). In the photograph are a fiddler, a lutenist, and a harpist, forming a kind of procession led by an official or cleric with a chain around his neck. Other panels show a bagpiper and a shawm player. Some or all the musicians are probably members of a group called the Confratrie Ministralorum Beate Marie Magdalene (the Brotherhood of Minstrels of Blessed Mary Magdalene), and so were almost certain to have played in St Mary Magdalene’s church.* Some scholars believe that, this being the case, the carvings of the instruments would have been quite realistic, unlike carvings of instrumentalists on gargoyles, for example, which were more likely to have been caricatures, and unlike angels carved in roofs, where ‘realism’ has to be aided by imagination and where the instruments may be generic. Alas! the wear and tear of time, together with the granite’s toughness, have scuppered our chances of making out much detail today.

Nevertheless, one of the joys of visiting old churches is the evidence they give of the activities of the past generations who built and used them. It’s good to find these musicians here and to think about the kinds of sounds they might have made in a market town in Cornwall some 500 years ago.

- - - - -

* St Mary herself, resting with her pot of ointment, is visible to the right of the musicians.

Tuesday, November 14, 2023

Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire

Beside the street opposite Chipping Campden’s 17th-century almshouses is this unusual feature. It now looks like a stretch of paved road that dips below the normal street level and it was originally full of water. This is a cart wash, and it dates to the early-19th century. Back then, mud could build up badly on cart wheels – not only on carts that had been in the fields, but on those hauled along rough and sometimes rutted roads or tracks. So the idea of a public cart wash was to enable carters to clean the mud off their wheels before entering the centre of town.

There was another use of the cart wash and this was to stand the vehicle in it for a while, to give the wheels a good soaking. Old-fashioned horse-drawn carts had wooden wheels protected by metal tyres around the rims. If the wheels got too dry, the tyres could loosen and fall off. Soaking the wheels was a way of making them expand a little, to tighten the tyres and keep the wooden wheels properly protected.

The world of horse-drawn carts and their maintenance seems remote now, but it’s not that long ago. I never knew my great uncle, whose business involved carting goods around rural north Lincolnshire, although my mother remembered him fondly. Just over a century ago, such people played an important role in rural communities, as did the men who built and repaired their carts. The Wheelwright’s Shop, George Sturt’s evocative 1923 account of this world of craftsmanship and toil, is well worth reading. Seeing Chipping Campden’s Cotswold stone cart wash brings it all back.

Wednesday, November 8, 2023

Ledbury, Herefordshire

Sweet

This beautiful sign in Ledbury has a special resonance for me, because I had a much-loved relative who was a confectioner. R, a cousin of my mother’s, could do the lot, from chocolate work to making boiled sweets, from seaside rock to luxurious coconut ice or fudge. For a while he had a shop next to a venue – a combined cinema and theatre – where famous stars performed. Many of them dropped in for something sweet and some came back whenever they were performing next door. The demise of live gigs there was a blow, and he moved on.

His wares were good enough to sell without advertisement, and his shop didn’t have a wonderful glass sign like this. But what a joy it is.* That graceful lettering with its gradually widening and narrowing stroke widths is a delight: how difficult it must have been to do that in glass. Just as good is the crazy-paving style background, made up of glass so richly coloured it reminds me of Fruit Gums.¶ I know, I know: there weren’t blue Fruit Gums. But the raspberry red, lemon yellow, lime green, and orange seem to fit the part.

Not knowing for sure the date of this glazing, I’m going to suggest a vague ‘early 20th century’. I like to imagine glazing like this lit from behind on a dark night, so that the colours glow. Bulbs placed behind the sign could also shine their light downwards, to illuminate the goods in the window, drawing the eyes of passers-by, making their mouths water, and luring them inside. Delicious!

- - - - -

* It will be even clearer if you click on the picture to enlarge it.

¶ Rowntree’s Fruit Gums: fruit sweets that were part of my childhood and which turn out to be still available, in the UK at least.

Thursday, November 2, 2023

Strand, London

Tea break

The last few months have seen me wind down my paid work as part of my preparation for retirement. This process has involved saying farewell to my time as a teacher of courses – I did my last in August – and I have just done what is probably the last of my various talks and lectures. I’ve enjoyed this activity hugely. One of the drawbacks of life as an author is that writing is a solitary activity. Getting out and speaking and teaching means I get out and meet people, mostly people I’d never have met otherwise. I’ll miss that, but I’ll not be sorry to give up the travelling. In the past, driving to a venue to teach or speak has had the bonus of taking me to new places and countryside too. But increasingly it is feeling like hard work.

My last talk happens to be one I call ‘Great British Brands’, a brief introduction to the history of a number of famous food and drink brands, a subject that caught my interest when I wrote a book about the history ofd shops and shopping, years ago. Among the companies featured in the talk is Twining’s, one of the most celebrated British tea brands, which has been going strong for more than 300 years, albeit these days as a part of a larger conglomerate. So here’s a picture of the entrance to Twining’s premises in London’s Strand, the site where the founder, Thomas Twining, set up Tom’s Coffee House in 1706.

Tom, who was from a family of Gloucestershire weavers, came with his family to London to find work, did his weaver’s apprenticeship, but decided that he’d prefer to work for one of London’s merchants instead. The merchant was handling shipments of tea, and Tom eventually went it alone in the tea trade. He succeeded because tea was newly fashionable and because he sold dry tea to women, who were not allowed into conventional coffee houses in London, which were men-only. This doorway is later than the original coffee house, and was built for Tom’s grandson, Richard Twining, in 1787. The two men in Chinese dress refer to the source of the tea and the lion symbolises Twining’s dry tea and coffee shop, which was known as the Golden Lion.

And so you see even a talk on food brands has been an excuse to show people memorable bits of architecture and design – from Cadbury’s factory at Bournville to shop signs advertising Hovis bread. For now, I’m not retiring from sharing similar things on this blog, for those who are interested enough to look and read about them over a cup of tea, and, I hope, go and see for themselves.

The last few months have seen me wind down my paid work as part of my preparation for retirement. This process has involved saying farewell to my time as a teacher of courses – I did my last in August – and I have just done what is probably the last of my various talks and lectures. I’ve enjoyed this activity hugely. One of the drawbacks of life as an author is that writing is a solitary activity. Getting out and speaking and teaching means I get out and meet people, mostly people I’d never have met otherwise. I’ll miss that, but I’ll not be sorry to give up the travelling. In the past, driving to a venue to teach or speak has had the bonus of taking me to new places and countryside too. But increasingly it is feeling like hard work.

My last talk happens to be one I call ‘Great British Brands’, a brief introduction to the history of a number of famous food and drink brands, a subject that caught my interest when I wrote a book about the history ofd shops and shopping, years ago. Among the companies featured in the talk is Twining’s, one of the most celebrated British tea brands, which has been going strong for more than 300 years, albeit these days as a part of a larger conglomerate. So here’s a picture of the entrance to Twining’s premises in London’s Strand, the site where the founder, Thomas Twining, set up Tom’s Coffee House in 1706.

Tom, who was from a family of Gloucestershire weavers, came with his family to London to find work, did his weaver’s apprenticeship, but decided that he’d prefer to work for one of London’s merchants instead. The merchant was handling shipments of tea, and Tom eventually went it alone in the tea trade. He succeeded because tea was newly fashionable and because he sold dry tea to women, who were not allowed into conventional coffee houses in London, which were men-only. This doorway is later than the original coffee house, and was built for Tom’s grandson, Richard Twining, in 1787. The two men in Chinese dress refer to the source of the tea and the lion symbolises Twining’s dry tea and coffee shop, which was known as the Golden Lion.

And so you see even a talk on food brands has been an excuse to show people memorable bits of architecture and design – from Cadbury’s factory at Bournville to shop signs advertising Hovis bread. For now, I’m not retiring from sharing similar things on this blog, for those who are interested enough to look and read about them over a cup of tea, and, I hope, go and see for themselves.

Sunday, October 29, 2023

Walford, Herefordshire

Not so primitive, 2

Spotted on the same day as the chapel in my previous post, this building is in Walford, between Brampton Bryan and Leintwardine in far northwest Herefordshire. It’s another Primitive Methodist chapel and, like the one in Weobley, it’s a brick building with a pitched roof and stone dressings around the windows and doors. And yet it looks very different from the Weobley chapel because it’s in the Gothic style – all the openings are pointed and those at the front have some extra elaboration in the form of carved terminations to the hood moulds over the windows and doorway. There’s also a charming quatrefoil-shaped opening in the gable, the frame of which contains the inscription, ‘Primitive Methodist Chapel 1866’.

The wing to the right was built as a schoolroom. Its glazing bars have a simpler pattern than those at the front of the chapel, but are still probably original. Both roofs are enhanced by curvaceous bargeboards of a kind I associate more with large suburban villas than Primitive Methodist Chapels, but why should the devil have all the good carpentry?

As can be seen from the signage, the chapel, the building is not longer used for worship, housing instead a gallery where drawings are exhibited. Chapels can make good gallery spaces, and this seems a dream use for such a building that is no longer required for its original purpose. Someone said that the latest art galleries, designed by starry architects and filled with works that are designed to shock or awe, are the cathedrals of our time. But I appreciate this chapel-gallery too.*

- - - - -

* See the gallery’s website for information about The Drawing Gallery and its exhibitions.

Spotted on the same day as the chapel in my previous post, this building is in Walford, between Brampton Bryan and Leintwardine in far northwest Herefordshire. It’s another Primitive Methodist chapel and, like the one in Weobley, it’s a brick building with a pitched roof and stone dressings around the windows and doors. And yet it looks very different from the Weobley chapel because it’s in the Gothic style – all the openings are pointed and those at the front have some extra elaboration in the form of carved terminations to the hood moulds over the windows and doorway. There’s also a charming quatrefoil-shaped opening in the gable, the frame of which contains the inscription, ‘Primitive Methodist Chapel 1866’.

The wing to the right was built as a schoolroom. Its glazing bars have a simpler pattern than those at the front of the chapel, but are still probably original. Both roofs are enhanced by curvaceous bargeboards of a kind I associate more with large suburban villas than Primitive Methodist Chapels, but why should the devil have all the good carpentry?

As can be seen from the signage, the chapel, the building is not longer used for worship, housing instead a gallery where drawings are exhibited. Chapels can make good gallery spaces, and this seems a dream use for such a building that is no longer required for its original purpose. Someone said that the latest art galleries, designed by starry architects and filled with works that are designed to shock or awe, are the cathedrals of our time. But I appreciate this chapel-gallery too.*

- - - - -

* See the gallery’s website for information about The Drawing Gallery and its exhibitions.

Tuesday, October 24, 2023

Weobley, Herefordshire

Not so primitive, 1

Following on from my previous post, here is another building in Weobley that I missed on my first visit. It’s the Methodist chapel, built in 1861, originally for the Primitive Methodists. The Primitive Methodists were a group founded in the early-19th century, who sought to focus on the core ideas of Methodism, which they felt that many Methodists were ignoring. They stressed in particular the role of the laity, worked to preach to the rural poor, and did not shy away from the political relevance of Christian ideas; they also adopted simple forms of worship and, often, of chapel architecture.

My mental picture of a Primitive Methodist chapel is a very plain building, perhaps built of brick, with a front comprising a pair of windows and a central door, topped with a hipped roof. However, the Primitives were not above a little architectural sophistication. This chapel has the simple brick front with two windows and a door, but this is elaborated with stone quoins plus rusticated stone blocks around the windows and doorway. These details succeed, in my opinion, in lifting the building above the mundane without indulging in what some of its early worshippers might have seen as Gothic flights of fancy. I find the result visually pleasing, and it’s pleasing, too, to see that the windows have retained their original glazing bars. No doubt the light they let in is a real asset when it comes to reading hymn books and Bibles – the chapel still used for worship, unlike at least two others I spotted in Herefordshire on my visit the other day.

Thursday, October 19, 2023

Weobley, Herefordshire

An educational legacy

I’d been to Weobley, one of Herefordshire’s best ‘black and white’ villages, before, but I’d somehow managed to miss the street that contains both the Methodist chapel and this, the Old Grammar School. This was a major omission on my part, for this building alone. It was erected in 1659 to accommodate a grammar school for boys that was founded in the same year by William Crowther, who left in his will not only money to build the school, but enough for an annuity to pay the master’s salary.

The building would have had one large room on the ground floor, where the lessons took place. Upstairs was a dormitory in which the pupils slept (there were 25 of them in the early-18th century), plus rooms for the master. It’s well built, with the vertical timbers set close together (a design known as ‘close-studding’) and plenty of pleasant touches – carved brackets, a couple of decorative heads (see the photograph below), turned shafts in the openings on each side of the porch, and the founder’s coat of arms above the entrance. The quality of the work has led some to suggest the renowned Herefordshire carpenter John Abel as the builder, although this, so far as I know, is speculation.

The building had a long life in educational use, which only came to an end in 1888. At this point it was sold as a house, which it still seems to be. So no more schoolboys intoning Latin declensions, no more the noise of 20-odd pairs of feet making there way upstairs to bed or downstairs to the schoolroom, no longer the experience (novel to us) of lessons in the building made of wood, wattle and daub. Just another timber-framed house of which Weobley can be more than proud.Detail of carvings above the doorway, Old Grammar School, Weobley

I’d been to Weobley, one of Herefordshire’s best ‘black and white’ villages, before, but I’d somehow managed to miss the street that contains both the Methodist chapel and this, the Old Grammar School. This was a major omission on my part, for this building alone. It was erected in 1659 to accommodate a grammar school for boys that was founded in the same year by William Crowther, who left in his will not only money to build the school, but enough for an annuity to pay the master’s salary.

The building would have had one large room on the ground floor, where the lessons took place. Upstairs was a dormitory in which the pupils slept (there were 25 of them in the early-18th century), plus rooms for the master. It’s well built, with the vertical timbers set close together (a design known as ‘close-studding’) and plenty of pleasant touches – carved brackets, a couple of decorative heads (see the photograph below), turned shafts in the openings on each side of the porch, and the founder’s coat of arms above the entrance. The quality of the work has led some to suggest the renowned Herefordshire carpenter John Abel as the builder, although this, so far as I know, is speculation.

The building had a long life in educational use, which only came to an end in 1888. At this point it was sold as a house, which it still seems to be. So no more schoolboys intoning Latin declensions, no more the noise of 20-odd pairs of feet making there way upstairs to bed or downstairs to the schoolroom, no longer the experience (novel to us) of lessons in the building made of wood, wattle and daub. Just another timber-framed house of which Weobley can be more than proud.Detail of carvings above the doorway, Old Grammar School, Weobley

Sunday, October 15, 2023

Chaceley, Gloucestershire

Worse things than serpents, or, Odd things in churches (17)

Finding this drum in a corner of St John’s church, Chaceley, made me wonder: was it some military relic,. put in the church for lack of anywhere else to keep it? Such an explanation seemed unlikely, in spite of the patriotic Hanoverian royal arms painted on the side of the instrument. The information available in the church offered a more likely story: that the drum was simply one of the instruments used in church music – it would have been played as part of an instrumental band that accompanied the singing of psalms, hymns, and the occasional anthem. Such bands were common between c. 1750 and c. 1850, before organs, harmoniums, and barrel organs started to become popular in parish churches. A common ensemble would consist mainly of stringed instruments (mainly violins and cellos), plus one or two woodwind – a clarinet, flute, and bassoon, perhaps. But such combinations were not fixed. In a small village especially, the church would get by with whatever and whoever was available.

This kind of instrumental accompaniment is sometimes called West gallery music, because the instrumentalists often played in the gallery at the west end of the church. The most famous literary evocation of such music is in Thomas Hardy’s novel Under the Greenwood Tree, in which the singers and musicians of Mellstock church (Mellstock is Hardy’s name for the real Dorset village of Stinsford) decry the coming fashion for harmoniums and barrel organs. Most of them agree that strings are best for church music, and some will admit that woodwinds have their place, even the unwieldy-looking bass instrument called the serpent (‘Yet there’s worse things than serpents’ as Mr Penny says). And drums? ‘Your drum-man is a rare bowel-shaker – good again,’ as another of Hardy’s characters puts it.

So if drum was available, a keen ‘bowel-shaker’ might well have been welcomed into the band. Even someone making a martial noise was better to the traditionalists of the 19th century than an organist or a player of the harmonium (‘that you blow wi’ your foot’). Bang on!

Wednesday, October 11, 2023

Croome, Worcestershire

A glance into the past

Early on in the history of this blog, I did a couple of posts about Croome Court, the 18th-century house of the earls of Coventry. What especially interested me was the number and variety of buildings in Croome’s landscape garden and the surrounding countryside, from the classical ‘Temple Greenhouse’ by Robert Adam to a circular panorama tower. Croome is a place I’ve been meaning to revisit for a while now, and I planned to do a post about the house and its 18th-century architecture but, as usual, something unexpected caught my eye. So, much as I enjoyed looking at the Georgian architecture of the great house, designed by Capability Brown and with interiors partly by Robert Adam, here at the heart of this 18th-century building is, of all things, a bit of timber-framed wall.

The 6th Earl built Croome Court as we know it, an elegant Palladian house with corner towers and a central classical portico, in the 1750s. But the central part was actually a rebuilding of the family’s earlier 17th-century brick-built house – the architect, Brown, rebuilt it using the old foundations, facing it in stone, laying out new rooms inside, and adding the corner towers and portico. The 17th-century house, however, had an even earlier, timber-framed house at its core, and it’s a fragment of this that I noticed as I walked around the building’s basement. One of the National Trust’s helpful guides, seeing me looking at this, pointed out details on the floor that showed the lines of early, long-demolished walls among the floor tiles.

And so Croome Court, so classically perfect, turned out to be a bit of an architectural jigsaw, as so many buildings do when you look carefully. I don’t know if it was a member of the Coventry family or one of the house’s later owners* or the National Trust who now run and maintain the building who left this small section of timber-framing exposed. But I was pleased that they’d done so, because it made me think of the house in a different way, one more true to its complex history.

- - - - -

* The ownership history of the house has been varied since the 1940s. Sold off by the family after World War II, it became successively home to a school, to the UK headquarters of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, to a property developer who planned to turn it into a hotel, and to another developer who lived in it for a while. The Croome Heritage Trust then took over the house in tandem with the National Trust, ensuring its survival.

Early on in the history of this blog, I did a couple of posts about Croome Court, the 18th-century house of the earls of Coventry. What especially interested me was the number and variety of buildings in Croome’s landscape garden and the surrounding countryside, from the classical ‘Temple Greenhouse’ by Robert Adam to a circular panorama tower. Croome is a place I’ve been meaning to revisit for a while now, and I planned to do a post about the house and its 18th-century architecture but, as usual, something unexpected caught my eye. So, much as I enjoyed looking at the Georgian architecture of the great house, designed by Capability Brown and with interiors partly by Robert Adam, here at the heart of this 18th-century building is, of all things, a bit of timber-framed wall.

The 6th Earl built Croome Court as we know it, an elegant Palladian house with corner towers and a central classical portico, in the 1750s. But the central part was actually a rebuilding of the family’s earlier 17th-century brick-built house – the architect, Brown, rebuilt it using the old foundations, facing it in stone, laying out new rooms inside, and adding the corner towers and portico. The 17th-century house, however, had an even earlier, timber-framed house at its core, and it’s a fragment of this that I noticed as I walked around the building’s basement. One of the National Trust’s helpful guides, seeing me looking at this, pointed out details on the floor that showed the lines of early, long-demolished walls among the floor tiles.

And so Croome Court, so classically perfect, turned out to be a bit of an architectural jigsaw, as so many buildings do when you look carefully. I don’t know if it was a member of the Coventry family or one of the house’s later owners* or the National Trust who now run and maintain the building who left this small section of timber-framing exposed. But I was pleased that they’d done so, because it made me think of the house in a different way, one more true to its complex history.

- - - - -

* The ownership history of the house has been varied since the 1940s. Sold off by the family after World War II, it became successively home to a school, to the UK headquarters of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, to a property developer who planned to turn it into a hotel, and to another developer who lived in it for a while. The Croome Heritage Trust then took over the house in tandem with the National Trust, ensuring its survival.

Friday, October 6, 2023

Leamington Spa, Warwickshire

The angular meander

Is there a pattern that says ‘Greece’ louder and more clearly than the ‘Greek key’? This motif takes the form of a continuous line that bends back on itself through a series of right-angles, before bending again to resume its forward course. It’s sometimes called the Greek fret, sometimes the meander, and some say its form derives from the Greek River Maeander (or Meander). It was widely used in the architecture of the Greek revival, a style popular in Britain during the decades on either side of 1800.

Here it is in the iron supports of the veranda that runs along the front of the houses in Lansdowne Crescent, Leamington. They were built in the mid 1830s to designs by local architect William Thomas. The uprights with their Greek key design ensure that the canopy above the veranda is held up securely, while also proclaiming the classical heritage of these town houses. The verandas were not so much for sitting out on – they are quite narrow – but more to provide shade for the almost south-facing rooms while also ensuring that if the floor-to-ceiling window is open, no one absentmindedly steps out and tumbles into the area below.

Soon after the residents moved in, Queen Victoria was on the throne and the fashion for elegant middle-class houses would turn from the classical to other styles – Italianate, Tudor revival, or Gothic. But the people who lived in Lansdowne Crescent in the mid-1830s (whether they were permanent residents or visitors who rented a house for the ‘season’, in order to make use of Leamington’s spa) must have delighted in their homes, which were both chic and Greek, courtesy of the angular meanders of their exterior ironwork.

Is there a pattern that says ‘Greece’ louder and more clearly than the ‘Greek key’? This motif takes the form of a continuous line that bends back on itself through a series of right-angles, before bending again to resume its forward course. It’s sometimes called the Greek fret, sometimes the meander, and some say its form derives from the Greek River Maeander (or Meander). It was widely used in the architecture of the Greek revival, a style popular in Britain during the decades on either side of 1800.

Here it is in the iron supports of the veranda that runs along the front of the houses in Lansdowne Crescent, Leamington. They were built in the mid 1830s to designs by local architect William Thomas. The uprights with their Greek key design ensure that the canopy above the veranda is held up securely, while also proclaiming the classical heritage of these town houses. The verandas were not so much for sitting out on – they are quite narrow – but more to provide shade for the almost south-facing rooms while also ensuring that if the floor-to-ceiling window is open, no one absentmindedly steps out and tumbles into the area below.

Soon after the residents moved in, Queen Victoria was on the throne and the fashion for elegant middle-class houses would turn from the classical to other styles – Italianate, Tudor revival, or Gothic. But the people who lived in Lansdowne Crescent in the mid-1830s (whether they were permanent residents or visitors who rented a house for the ‘season’, in order to make use of Leamington’s spa) must have delighted in their homes, which were both chic and Greek, courtesy of the angular meanders of their exterior ironwork.

Sunday, October 1, 2023

Leamington Spa, Warwickshire

Tea in the park

Visiting Leamington Spa recently, I was particularly struck by the decorative ironwork on many of the buildings. Much of this was from the town’s Regency heyday – the iron balconies that resemble those in Cheltenham and Brighton, although in many cases with different designs. One example from a later period, however, stands out: the ironwork that makes the Aviary Café in Jephson Gardens so special.

Several of the structures in this beautiful urban park have a serious memorial purpose. This paragon of ornamental park structures is different. It was built in 1899 simply to house tea rooms – there’s an Edwardian-looking photograph online showing elegantly dressed people relaxing in front of the café amid a small copse of umbrellas that shade outdoor tables from the sun. At some point in the 20th century, the café closed and was turned into an aviary, but by the last decades of the 20th century this had closed and the building fell into disuse and disrepair. As part, I believe, of a millennium project to enhance the park, it was restored and turned back into a café, in which form it still seems to be thriving.

At the front, the roof is held up by slender iron columns, allowing it to overhang and shelter a narrow porch or veranda, which now houses several small café tables. Look up, and you see the splendour – several metres of intricate iron latticework filling the spandrels, cornices, and the space beneath the central gable. Look closely, and you see multifoil arches, patterns of circles and scrolls, and iron finials at the ends of the eaves and at the gable’s peak.

The whole thing is a showpiece of the Victorian metalworker’s art and the epitome of the ornamental public park building of the period. It’s up there with the best bandstands and other pleasure buildings, with decoration that at once enhances the view and catches the eye, beckoning us in to sample the delights within. To my mind, it’s a small architectural triumph.

Visiting Leamington Spa recently, I was particularly struck by the decorative ironwork on many of the buildings. Much of this was from the town’s Regency heyday – the iron balconies that resemble those in Cheltenham and Brighton, although in many cases with different designs. One example from a later period, however, stands out: the ironwork that makes the Aviary Café in Jephson Gardens so special.

Several of the structures in this beautiful urban park have a serious memorial purpose. This paragon of ornamental park structures is different. It was built in 1899 simply to house tea rooms – there’s an Edwardian-looking photograph online showing elegantly dressed people relaxing in front of the café amid a small copse of umbrellas that shade outdoor tables from the sun. At some point in the 20th century, the café closed and was turned into an aviary, but by the last decades of the 20th century this had closed and the building fell into disuse and disrepair. As part, I believe, of a millennium project to enhance the park, it was restored and turned back into a café, in which form it still seems to be thriving.

At the front, the roof is held up by slender iron columns, allowing it to overhang and shelter a narrow porch or veranda, which now houses several small café tables. Look up, and you see the splendour – several metres of intricate iron latticework filling the spandrels, cornices, and the space beneath the central gable. Look closely, and you see multifoil arches, patterns of circles and scrolls, and iron finials at the ends of the eaves and at the gable’s peak.

The whole thing is a showpiece of the Victorian metalworker’s art and the epitome of the ornamental public park building of the period. It’s up there with the best bandstands and other pleasure buildings, with decoration that at once enhances the view and catches the eye, beckoning us in to sample the delights within. To my mind, it’s a small architectural triumph.

Tuesday, September 26, 2023

Nottingham

The long view

Among the multitude of things that pop up on social media, one I take notice of is a blog produced by Historic England. For each post it takes a theme or an architectural style and gives a handful of outstanding examples. The theme the other day was Art Nouveau architecture in England, and I was pleased to see that Historic England’s gurus had picked four of my personal favourites: the elegant if eccentric Turkey Café in Leicester (all pale stripes and gobblers), the Royal Arcade in Norwich (with its air of Edwardian luxury) and the glorious former printing works of Everard’s in Bristol (with a facade that illustrates two luminaries of the craft of printing, Johannes Gutenberg and William Morris). All of these have featured on this blog in the past and all, by the way, are adorned with tiles designed by W. J. Neatby of Royal Doulton. However, another favourite of mine selected by Historic England was a building I’ve not blogged until now.

When I last passed by this imposing shop in the centre of Nottingham, it was a branch of the women’s clothes store Zara. It started out as something quite different, because it belonged to Boot’s the chemist – in fact it was their largest Nottingham branch in the early 1900s when it was built. As Boot’s was a Nottingham company, it was what modern retailers might called their flagship store. The upper part of the building at first glance looks like a baroque palace, with a dome to make the corner into a landmark. However some of the detailing, including the youthful figures hat support the balcony and cornices, together with some of the terracotta foliage, and the gently swelling columns that frame some of the window openings, are all of their time. It’s the ground-level shop front, though, that really looks Art Nouveau. This was the style of the sinuous curve, and the wooden window frames have curves in abundance, especially in the transom lights, the upper sections of the window, which have heart-shaped and tear-shaped panes, supported by a framework that’s both curvaceous and richly carved. Looking up as one enters, a similar pattern of glazing bars , this time with mirror glass, fills the ceiling, making the lobbies lighter.

It’s a lavish design, showing how Boot’s and their architect, Albert Nelson Bromley, made a special effort for this important store. The building was subdivided to accommodate the company’s variety of departments – everything from photographic processing to a lending library, as well as Boot’s core business of pharmaceuticals and cosmetics, but this interior was reconstructed in 1972 after the chemists had vacated the building. The shop front remains, showing how it was built to last by a company that, unlike so many modern retailers who put up flimsy frontages because they known everything will be redesigned in a few years, took the long view. Looking up in the lobby, Boots, Nottingham (now Zara)

Thursday, September 21, 2023

Birmingham

Turning a corner, 2

Few buildings turn a corner with such grandeur as this one in Birmingham’s Constitution Hill. It dates from the 1890s and was designed architects William Doubleday* and James R. Shaw for H. B. Sale, a firm of die-sinkers. The plan was to have offices and shops on the ground floor with each upper floor taken up by one large workshop, plus an office in the corner tower. Five floors were planned, but the fifth was not added until the mid-20th century, hence the difference in style.

The exterior is built of red brick with a rich array of terracotta dressings – foliage, flowers, and medieval-style heads all feature and the top of the building as originally constructed was given some distinction with the row of small curved gables still present in front of the 20th-century top storey. The stylistic label given by English Heritage’s short ‘Informed Conservation’ book about the district is Spanish Romanesque-style. The stand-out feature is the tower, which is still a landmark on the junction of Constitution Hill and Hampton Street. Each storey of the tower has a different kind of opening, from the first floor† upwards: trefoil, slightly wasp-waisted arches; flat-topped openings; windows topped with ogees; semicircular openings; and quatrefoils in the tiny gables around the dome. The tower also displays the owner’s name,¶ standing proud from the band of foliate decoration – a popular late-19th century effect that I always admire. Finally, the ogee dome at the top, with its fish-scale surface, provides a pleasing climax, although it’s slightly hidden by the gables and finials that surround it. What a glorious building. I hope its owners are soon able to remove the plants that are taking root towards the top of the tower, so that it can continue to provide the area with a landmark and an admirable collection of exuberant architectural decoration.

- - - - -

* William Doubleday was based in Wolverhampton when this building was designed; he later moved to Birmingham.

† American second floor.

Few buildings turn a corner with such grandeur as this one in Birmingham’s Constitution Hill. It dates from the 1890s and was designed architects William Doubleday* and James R. Shaw for H. B. Sale, a firm of die-sinkers. The plan was to have offices and shops on the ground floor with each upper floor taken up by one large workshop, plus an office in the corner tower. Five floors were planned, but the fifth was not added until the mid-20th century, hence the difference in style.

The exterior is built of red brick with a rich array of terracotta dressings – foliage, flowers, and medieval-style heads all feature and the top of the building as originally constructed was given some distinction with the row of small curved gables still present in front of the 20th-century top storey. The stylistic label given by English Heritage’s short ‘Informed Conservation’ book about the district is Spanish Romanesque-style. The stand-out feature is the tower, which is still a landmark on the junction of Constitution Hill and Hampton Street. Each storey of the tower has a different kind of opening, from the first floor† upwards: trefoil, slightly wasp-waisted arches; flat-topped openings; windows topped with ogees; semicircular openings; and quatrefoils in the tiny gables around the dome. The tower also displays the owner’s name,¶ standing proud from the band of foliate decoration – a popular late-19th century effect that I always admire. Finally, the ogee dome at the top, with its fish-scale surface, provides a pleasing climax, although it’s slightly hidden by the gables and finials that surround it. What a glorious building. I hope its owners are soon able to remove the plants that are taking root towards the top of the tower, so that it can continue to provide the area with a landmark and an admirable collection of exuberant architectural decoration.

- - - - -

* William Doubleday was based in Wolverhampton when this building was designed; he later moved to Birmingham.

† American second floor.

¶ You can enlarge the picture by clicking on it, which might make this a little easier to see.

Saturday, September 16, 2023

Birmingham

Turning a corner, 1

This is one of my favourite buildings that I saw on a stroll around Birmingham’s jewellery quarter a while back. It’s not a factory or anything to do with the jewellery business, however: it was built as a pub at the end of the 1860s, that decade when Victorian architecture became more jazzy, colourful and free than most of what went before. The style of Gothic is described by the Pevsner City Guide to Birmingham as ‘very Ruskinian’. In other words there are lots of pointed arches in rows, built in a polychrome mix of red, white and grey (aka ‘blue’) bricks; there are natty details like the small oriel window at the corner and the octagonal turret just visible in my photograph; and there are twin openings divided by slender shafts with carved capitals. All of these details were in the architectural air at this time thanks to the writings of John Ruskin, whose accounts of Venetian Gothic (in books such as The Stones of Venice, which came out in the early 1850s) were increasingly influential.

So far, so good. Whether Ruskin would have approved of this building is another matter. He seems to have had a downer on the kind of dissipation sometimes associated with pubs and taverns, and on genre artists, such as Jan Steen, who painted tavern scenes. But many of us will take a different view. Why should a pub not have a stunning facade, designed with flair, built with care, and enhancing the streetscape? If places of worship or education can have glorious polychrome brick frontages, why not places of hospitality too? I thoroughly approve, and I approve too of the fact that the building has been restored to make the most of its glorious exterior.

Another thing I admire about this building is the swagger with which it occupies a corner plot that is challenging architecturally. Corner plots are good for business, because a site on a junction allows the building to be seen and approached from several different directions. But a tapering cake-slice of a plot like this one is not always easy when it comes to designing the building – how does the structure ‘turn the corner’ visually, and what do you do with the tiny sliver that faces directly on to the junction? Placing the entrance there can be a good solution. Giving the entrance a bit of emphasis by adding the oriel window above (with its cusp-headed opening to make it extra ornate, a pattern echoed in the window on the upper floor) is highly effective visually. Here’s to Victorian brickwork, ingenuity, and that quality of vigour and distinctiveness they called ‘go’!

This is one of my favourite buildings that I saw on a stroll around Birmingham’s jewellery quarter a while back. It’s not a factory or anything to do with the jewellery business, however: it was built as a pub at the end of the 1860s, that decade when Victorian architecture became more jazzy, colourful and free than most of what went before. The style of Gothic is described by the Pevsner City Guide to Birmingham as ‘very Ruskinian’. In other words there are lots of pointed arches in rows, built in a polychrome mix of red, white and grey (aka ‘blue’) bricks; there are natty details like the small oriel window at the corner and the octagonal turret just visible in my photograph; and there are twin openings divided by slender shafts with carved capitals. All of these details were in the architectural air at this time thanks to the writings of John Ruskin, whose accounts of Venetian Gothic (in books such as The Stones of Venice, which came out in the early 1850s) were increasingly influential.

So far, so good. Whether Ruskin would have approved of this building is another matter. He seems to have had a downer on the kind of dissipation sometimes associated with pubs and taverns, and on genre artists, such as Jan Steen, who painted tavern scenes. But many of us will take a different view. Why should a pub not have a stunning facade, designed with flair, built with care, and enhancing the streetscape? If places of worship or education can have glorious polychrome brick frontages, why not places of hospitality too? I thoroughly approve, and I approve too of the fact that the building has been restored to make the most of its glorious exterior.

Another thing I admire about this building is the swagger with which it occupies a corner plot that is challenging architecturally. Corner plots are good for business, because a site on a junction allows the building to be seen and approached from several different directions. But a tapering cake-slice of a plot like this one is not always easy when it comes to designing the building – how does the structure ‘turn the corner’ visually, and what do you do with the tiny sliver that faces directly on to the junction? Placing the entrance there can be a good solution. Giving the entrance a bit of emphasis by adding the oriel window above (with its cusp-headed opening to make it extra ornate, a pattern echoed in the window on the upper floor) is highly effective visually. Here’s to Victorian brickwork, ingenuity, and that quality of vigour and distinctiveness they called ‘go’!

Thursday, September 7, 2023

Muchelney, Somerset

Devoted to baser things

Dedicated as they were to higher things – prayer, the celebration of the Office at the canonical hours, the copying of books, especially holy scripture, and so on – monks needed also to cater for the needs of their bodies, from healthcare and food to lavatories and drains. Monastic drains often leave their traces, because they were carefully built and engineered, and set at or below ground level, so drainage channels often survive where standing buildings have disappeared. The lavatories that connect to these drains, by contrast, usually vanish. This makes the medieval lavatory building at Muchelney Abbey, probably built some time after 1268*, a rare survival.

The latrine block stands out because it’s two storeys high and has a striking thatched roof, although it is said that the roof was probably originally covered with slates.† The upper floor has a gap all the way along one side, where the wooden structures of the lavatories, together with partitions between each one, were fixed. This arrangement allowed the waste material to fall to the drain directly below, where it was flushed away using water from the abbey’s conduit. However, the flow from the conduit was probably not very fast, as a look from the upper flor down to the drain (as in my second photograph) shows a row of arches at the bottom, through which the monastic servants, or the monks themselves, could clean the drainage channel.

When it was built, the latrine block formed one end of the eastern range of the cloister. Next to it on the upper floor was the monastic dormitory or dorter – this proximity of lavatory and dormitory was standard, and the lavatory is often known as the reredorter. The abbey’s dissolution in 1538 led to the decay of most of the buildings, but this block was retained and used as a farm building. The change of use ensured its survival, giving us a special insight into one way in which medieval monks catered for the more mundane aspects of their everyday life.

- - - - -

* This date is based on tree-ring analysis of ancient timbers.

† I’m indebted to English Heritage’s guidebook to the monastery for much of my information about the building.

Dedicated as they were to higher things – prayer, the celebration of the Office at the canonical hours, the copying of books, especially holy scripture, and so on – monks needed also to cater for the needs of their bodies, from healthcare and food to lavatories and drains. Monastic drains often leave their traces, because they were carefully built and engineered, and set at or below ground level, so drainage channels often survive where standing buildings have disappeared. The lavatories that connect to these drains, by contrast, usually vanish. This makes the medieval lavatory building at Muchelney Abbey, probably built some time after 1268*, a rare survival.

The latrine block stands out because it’s two storeys high and has a striking thatched roof, although it is said that the roof was probably originally covered with slates.† The upper floor has a gap all the way along one side, where the wooden structures of the lavatories, together with partitions between each one, were fixed. This arrangement allowed the waste material to fall to the drain directly below, where it was flushed away using water from the abbey’s conduit. However, the flow from the conduit was probably not very fast, as a look from the upper flor down to the drain (as in my second photograph) shows a row of arches at the bottom, through which the monastic servants, or the monks themselves, could clean the drainage channel.

When it was built, the latrine block formed one end of the eastern range of the cloister. Next to it on the upper floor was the monastic dormitory or dorter – this proximity of lavatory and dormitory was standard, and the lavatory is often known as the reredorter. The abbey’s dissolution in 1538 led to the decay of most of the buildings, but this block was retained and used as a farm building. The change of use ensured its survival, giving us a special insight into one way in which medieval monks catered for the more mundane aspects of their everyday life.

- - - - -

* This date is based on tree-ring analysis of ancient timbers.

† I’m indebted to English Heritage’s guidebook to the monastery for much of my information about the building.

Thursday, August 31, 2023

Muchelney, Somerset

A glimpse of the heavens

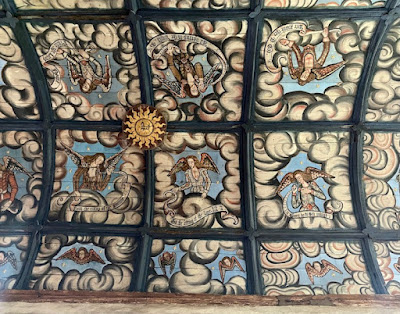

En route across Somerset, I decided to stop at Muchelney, where I’d not been for years. I planned to revisit the medieval abbey, but was also drawn to the adjacent but quite separate parish church of Saints Peter and Paul. The church is late-15th century, like so many in Somerset, but what I most wanted to see again was a later embellishment, the 17th-century ribbed and boarded ceiling of the nave, with its wonderful painted panels of angels looking down from the clouds.

I have not seen anything else quite like this ceiling (the angels in the church ceiling at Bromfield, Shropshire, come closest, but I’d say they are slightly later and in a different style). Each panel at Mucheleny is edged with clouds, which swirl like cotton wool or whipped cream, but are edged in darker shades. English clouds, of course, often combine the hopeful white with the threatening grey, but not quite in the stylized way of these ceiling paintings, and the stylization is part of their charm, which is easier to appreciate if you click on the image to enlarge it.

I find the angels charming too. They stand behind the clouds, and look down through the gaps between them; behind each figure is blue sky dotted with tiny stars, suggesting the angels are in a heavenly realm far above the clouds, farther still from us earthbound humans. They’re a far cry from medieval angels of any kind; neither are they like chaste Victorian angels. They have boldly painted faces, shoulder-length hair, and perky wings and they are are clothed in something like Elizabethan or Jacobean dresses, but in what Pevsner describes as ‘extreme décolletage’. The contours of their breasts vary – some look markedly rounded and suggest the human female form, some are less so. Those who feel compelled to explain such things suggest that their revealing costumes suggest their innocence, which sounds like a modern explainer trying very hard to justify what they see as inappropriate. Authorities such as Pevsner and the people who wrote the listing description for the church, avoid explanation altogether. I’d say anything that purports to be an explanation is at best informed guesswork.

The messages spoken by the angels, written on scrolls that they hold, are clear enough. ‘Good will towards men’, ‘Wee praise thee O God’, ‘All nations in the world…praise the Lords Name’, and so on. The sun, a golden roundel set at the intersection of four panels, looks on approvingly. From the floor below, I look up with similar approval at the whole ceiling – with more than approval indeed and with pleasure at another example of how the art of English churches can be colourful, unexpected, and full of joy.

En route across Somerset, I decided to stop at Muchelney, where I’d not been for years. I planned to revisit the medieval abbey, but was also drawn to the adjacent but quite separate parish church of Saints Peter and Paul. The church is late-15th century, like so many in Somerset, but what I most wanted to see again was a later embellishment, the 17th-century ribbed and boarded ceiling of the nave, with its wonderful painted panels of angels looking down from the clouds.

I have not seen anything else quite like this ceiling (the angels in the church ceiling at Bromfield, Shropshire, come closest, but I’d say they are slightly later and in a different style). Each panel at Mucheleny is edged with clouds, which swirl like cotton wool or whipped cream, but are edged in darker shades. English clouds, of course, often combine the hopeful white with the threatening grey, but not quite in the stylized way of these ceiling paintings, and the stylization is part of their charm, which is easier to appreciate if you click on the image to enlarge it.

I find the angels charming too. They stand behind the clouds, and look down through the gaps between them; behind each figure is blue sky dotted with tiny stars, suggesting the angels are in a heavenly realm far above the clouds, farther still from us earthbound humans. They’re a far cry from medieval angels of any kind; neither are they like chaste Victorian angels. They have boldly painted faces, shoulder-length hair, and perky wings and they are are clothed in something like Elizabethan or Jacobean dresses, but in what Pevsner describes as ‘extreme décolletage’. The contours of their breasts vary – some look markedly rounded and suggest the human female form, some are less so. Those who feel compelled to explain such things suggest that their revealing costumes suggest their innocence, which sounds like a modern explainer trying very hard to justify what they see as inappropriate. Authorities such as Pevsner and the people who wrote the listing description for the church, avoid explanation altogether. I’d say anything that purports to be an explanation is at best informed guesswork.

The messages spoken by the angels, written on scrolls that they hold, are clear enough. ‘Good will towards men’, ‘Wee praise thee O God’, ‘All nations in the world…praise the Lords Name’, and so on. The sun, a golden roundel set at the intersection of four panels, looks on approvingly. From the floor below, I look up with similar approval at the whole ceiling – with more than approval indeed and with pleasure at another example of how the art of English churches can be colourful, unexpected, and full of joy.

Thursday, August 24, 2023

Stanton, Gloucestershire

Sheepdogs, or, Odd things in churches (16)

I can’t remember when I first went inside the church of St Michael and All Angels, Stanton, in the north Cotswolds, but I think I already knew the story behind the bench-end in my photograph. Perhaps I knew the story from the Gloucestershire volume of Arthur Mee’s series, ‘The King’s England’, probably the only book that my parents had that would have held such a historical tidbit: ‘It may be that when Wesley preached in this place there listened to him shepherds from the hills who would tie their dogs to the ends of the benches, which still have the marks of the chafing of the chains which held the dogs.’ Such marks can certainly be seen on the bench end in my picture, perhaps from the chains themselves or from a metal ring to which chains were attached.

Can this be true? It’s certainly plausible. For centuries, Cotswold farms were the sheep farms par excellence of England. For years I’ve lived in this part of the country and there are still plenty of sheep farmed around here. Shepherds might these days ride around on quad bikes or in 4 x 4s, and wherever they go their dogs go with them. In church, in the 18th century or earlier, one can imagine the chained dogs excited on their weekly meeting with the neighbours pulling on their chains and chafing at the woodwork before settling down quietly by the time the service began. We’re often told that Cotswold churches (like many in Suffolk and other areas) were built from the proceeds of the wool trade. It’s good to be reminded that none of that money could have been made without the people who raised the sheep – and the animals that rounded them up.

Tuesday, August 22, 2023

Withypool, Somerset

Pump heaven

I’m not quite sure why I like old petrol pumps and garages. As far as the pumps are concerned it’s partly, I think, nostalgia and partly design – the lovely advertising globes on the tops of the pumps and the lines of the pumps themselves, which altered from one decade to the next as fashions changed. I think these Beckmeter pumps in the village of Withypool are probably from the 1960s. The shape, all straight lines, and the frames of chrome around the dials certainly look as if they’re from that decade, and online sources suggest I’m right. These pumps would be at home in front of a flat-roofed building with a large area of plate glass on the front. By the 1970s, similar-shaped pumps were still fashionable, but they increasingly had digital displays – the ones in which the digits were set on cylinders that rotated, bringing the next number gradually to the front. The star system for rating petrol (the pump in the foreground has two stars) came in during 1967, so that fits too, although the panel at the top where the stars are located was probably something that the garage owner or petrol company could change with ease. The shell-shaped globes, of course, are throwbacks to an earlier era. Shell globes in a similar design go back to 1929; the details of the design evolved, and the Shell globes were fitted to all kinds of different pumps.

Beckmeter pumps were ubiquitous back in the sixties and seventies. The company was founded as a general engineering concern in the Victorian era, and they gradually came to specialise in water meters and vales. When cars became increasingly common, in the interwar period, Beck’s adapted their water meter designs for use with petrol and soon manufacturing petrol pumps was a major part of their business. Of course these pumps lasted for years, and it was possible in, say, the 1980s, to find 30- or 40-year old pumps dispensing fuel. Hence their survival at filling stations like this one, long closed, in a remote Exmoor village.

I find the sight of them still lined up at a stone-built filling station, its woodwork painted to match the red of the Shell colours, very satisfying. Even more satisfying is that there’s an even older (1940s or 1950s) Avery-Hardoll pump (photo below) just across the road. Again, this one, now missing its globe, appears typical of its time – the tapering shape of the pump body and the script-style lettering of the Avery-Hardoll name look the part and the period.

Now there’s as much of a demand for coffee as for petrol, the forecourt with the Beckmeter pumps at Withypool has been taken over by a table, and refreshment is available from the building next door. So there’s a good reason for cyclists and walkers to stop here as well as motorists, and a good reason, I’d argue, for all of them to admire these examples of historical engineering and design.

I’m not quite sure why I like old petrol pumps and garages. As far as the pumps are concerned it’s partly, I think, nostalgia and partly design – the lovely advertising globes on the tops of the pumps and the lines of the pumps themselves, which altered from one decade to the next as fashions changed. I think these Beckmeter pumps in the village of Withypool are probably from the 1960s. The shape, all straight lines, and the frames of chrome around the dials certainly look as if they’re from that decade, and online sources suggest I’m right. These pumps would be at home in front of a flat-roofed building with a large area of plate glass on the front. By the 1970s, similar-shaped pumps were still fashionable, but they increasingly had digital displays – the ones in which the digits were set on cylinders that rotated, bringing the next number gradually to the front. The star system for rating petrol (the pump in the foreground has two stars) came in during 1967, so that fits too, although the panel at the top where the stars are located was probably something that the garage owner or petrol company could change with ease. The shell-shaped globes, of course, are throwbacks to an earlier era. Shell globes in a similar design go back to 1929; the details of the design evolved, and the Shell globes were fitted to all kinds of different pumps.

Beckmeter pumps were ubiquitous back in the sixties and seventies. The company was founded as a general engineering concern in the Victorian era, and they gradually came to specialise in water meters and vales. When cars became increasingly common, in the interwar period, Beck’s adapted their water meter designs for use with petrol and soon manufacturing petrol pumps was a major part of their business. Of course these pumps lasted for years, and it was possible in, say, the 1980s, to find 30- or 40-year old pumps dispensing fuel. Hence their survival at filling stations like this one, long closed, in a remote Exmoor village.

I find the sight of them still lined up at a stone-built filling station, its woodwork painted to match the red of the Shell colours, very satisfying. Even more satisfying is that there’s an even older (1940s or 1950s) Avery-Hardoll pump (photo below) just across the road. Again, this one, now missing its globe, appears typical of its time – the tapering shape of the pump body and the script-style lettering of the Avery-Hardoll name look the part and the period.

Now there’s as much of a demand for coffee as for petrol, the forecourt with the Beckmeter pumps at Withypool has been taken over by a table, and refreshment is available from the building next door. So there’s a good reason for cyclists and walkers to stop here as well as motorists, and a good reason, I’d argue, for all of them to admire these examples of historical engineering and design.

Thursday, August 17, 2023

Devizes, Wiltshire

Landmark base

I’ve passed this building a number of times when driving into or through Devizes in Wiltshire – one can’t fail to notice it, but it’s one of those buildings that is easy to pass by because you’re on the way to somewhere else. Coming out of the town the other week, I resolved to find a place to stop, have a closer look, and take a photograph. I knew little about it except that it was a former army barracks and that it was built in the late-19th century.

Its original role dates back to a series of reforms of the British army undertaken in the 1860s and 70s by the Liberal Prime Minister W. E. Gladstone and his Secretary of State for War, Edward Cardwell. The reforms involved abolishing the practice of buying commissions in the army, changing the way the War Office worked, and setting up reserve forces based in Britain. The barracks in Devizes were home to one of these forces, and was named after the illustrious cavalry commander John Le Marchant. For a long period the building was home to the Wiltshire Regiment, although during World War II it was used as a prisoner of war camp.

The castle-like architecture clearly signals the barracks’ military function – the part in my photograph is clearly built to resemble a castle keep, although longer blocks running to the left and behind this ‘keep’ are less military looking. The long blocks are the barracks themselves – the accommodation for the soldiers. The keep building contained a guard room, detention cells, and storage areas and armouries. The keep is a highly symbolic part of the complex. It is gratifying that it has survived the closure of the barracks and the eventual conversion of the site to housing – a structure that both embodies the past and reminds people today of the old phrase about an Englishman’s home being his castle.

I’ve passed this building a number of times when driving into or through Devizes in Wiltshire – one can’t fail to notice it, but it’s one of those buildings that is easy to pass by because you’re on the way to somewhere else. Coming out of the town the other week, I resolved to find a place to stop, have a closer look, and take a photograph. I knew little about it except that it was a former army barracks and that it was built in the late-19th century.