A glimpse of the heavens

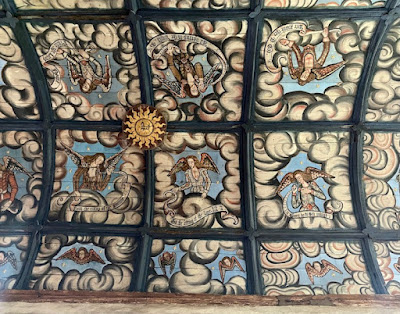

En route across Somerset, I decided to stop at Muchelney, where I’d not been for years. I planned to revisit the medieval abbey, but was also drawn to the adjacent but quite separate parish church of Saints Peter and Paul. The church is late-15th century, like so many in Somerset, but what I most wanted to see again was a later embellishment, the 17th-century ribbed and boarded ceiling of the nave, with its wonderful painted panels of angels looking down from the clouds.

I have not seen anything else quite like this ceiling (the angels in the church ceiling at Bromfield, Shropshire, come closest, but I’d say they are slightly later and in a different style). Each panel at Mucheleny is edged with clouds, which swirl like cotton wool or whipped cream, but are edged in darker shades. English clouds, of course, often combine the hopeful white with the threatening grey, but not quite in the stylized way of these ceiling paintings, and the stylization is part of their charm, which is easier to appreciate if you click on the image to enlarge it.

I find the angels charming too. They stand behind the clouds, and look down through the gaps between them; behind each figure is blue sky dotted with tiny stars, suggesting the angels are in a heavenly realm far above the clouds, farther still from us earthbound humans. They’re a far cry from medieval angels of any kind; neither are they like chaste Victorian angels. They have boldly painted faces, shoulder-length hair, and perky wings and they are are clothed in something like Elizabethan or Jacobean dresses, but in what Pevsner describes as ‘extreme décolletage’. The contours of their breasts vary – some look markedly rounded and suggest the human female form, some are less so. Those who feel compelled to explain such things suggest that their revealing costumes suggest their innocence, which sounds like a modern explainer trying very hard to justify what they see as inappropriate. Authorities such as Pevsner and the people who wrote the listing description for the church, avoid explanation altogether. I’d say anything that purports to be an explanation is at best informed guesswork.

The messages spoken by the angels, written on scrolls that they hold, are clear enough. ‘Good will towards men’, ‘Wee praise thee O God’, ‘All nations in the world…praise the Lords Name’, and so on. The sun, a golden roundel set at the intersection of four panels, looks on approvingly. From the floor below, I look up with similar approval at the whole ceiling – with more than approval indeed and with pleasure at another example of how the art of English churches can be colourful, unexpected, and full of joy.

Showing posts with label angels. Show all posts

Showing posts with label angels. Show all posts

Thursday, August 31, 2023

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

Bromfield, Shropshire

In the high and holy place

It’s the 1670s. The English Civil Wars have come and gone and the Stuart monarchy has been restored. In London, the great fire of 1666 has left its trail of damage, but the capital is being rebuilt. Wren’s new city churches are showing people how a kind of plain classical style can be adapted to church design. People are used to simple interiors, a minimum of imagery, and texts on the wall. If there is ceiling decoration, for example, it’s plasterwork not a million miles away from the kind of thing found in country houses of the period.

But English architecture can always produce something against the grain, something that throws away the rulebook. In the unlikely setting of the Shropshire countryside near Ludlow is a startling example. St Mary the Virgin, Bromfield, is a medieval parish church, once a Benedictine priory, originally built in the mid-12th century with later additions from the 13th and 16th centuries. There’s a solid-looking stone tower at the northwest corner, a nave, an aisle, a chancel – nothing unusual-sounding about all that.

What is unusual is the chancel ceiling, a celestial phantasmagoria of angels and clouds, each angel with a scroll bearing a Biblical quotation. This heavenly host was painted in about 1672 by Thomas Francis of Aston-by-Sutton, Cheshire. It combines the period’s taste for texts with a kind of angelic imagery that’s like little else. The angels are a varied bunch, some apparently naked, others draped in rural homespun. The scrolls bearing the texts curl this way and that across the sky.

At the centre, amongst the English country angels, the fluffy clouds, and the eccentrically scrolling texts, is a bit of Latin. It’s a diagrammatic explanation of one of Christianity’s greatest puzzles: the Trinity. If you follow the diagram, which is often known as the Shield of the Trinity, you will read, around the edge, that the Son is not the Father, who is not the Holy Spirit. But if you read inwards towards the centre you will discover that each of these is God. The whole ceiling is a remarkable combination of English and Latin, angels and clouds, folk art and exegesis. It’s mixed up but wonderfully surprising. And its charm is unique.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)