Devoted to baser things

Dedicated as they were to higher things – prayer, the celebration of the Office at the canonical hours, the copying of books, especially holy scripture, and so on – monks needed also to cater for the needs of their bodies, from healthcare and food to lavatories and drains. Monastic drains often leave their traces, because they were carefully built and engineered, and set at or below ground level, so drainage channels often survive where standing buildings have disappeared. The lavatories that connect to these drains, by contrast, usually vanish. This makes the medieval lavatory building at Muchelney Abbey, probably built some time after 1268*, a rare survival.

The latrine block stands out because it’s two storeys high and has a striking thatched roof, although it is said that the roof was probably originally covered with slates.† The upper floor has a gap all the way along one side, where the wooden structures of the lavatories, together with partitions between each one, were fixed. This arrangement allowed the waste material to fall to the drain directly below, where it was flushed away using water from the abbey’s conduit. However, the flow from the conduit was probably not very fast, as a look from the upper flor down to the drain (as in my second photograph) shows a row of arches at the bottom, through which the monastic servants, or the monks themselves, could clean the drainage channel.

When it was built, the latrine block formed one end of the eastern range of the cloister. Next to it on the upper floor was the monastic dormitory or dorter – this proximity of lavatory and dormitory was standard, and the lavatory is often known as the reredorter. The abbey’s dissolution in 1538 led to the decay of most of the buildings, but this block was retained and used as a farm building. The change of use ensured its survival, giving us a special insight into one way in which medieval monks catered for the more mundane aspects of their everyday life.

- - - - -

* This date is based on tree-ring analysis of ancient timbers.

† I’m indebted to English Heritage’s guidebook to the monastery for much of my information about the building.

Showing posts with label Muchelney. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Muchelney. Show all posts

Thursday, September 7, 2023

Thursday, August 31, 2023

Muchelney, Somerset

A glimpse of the heavens

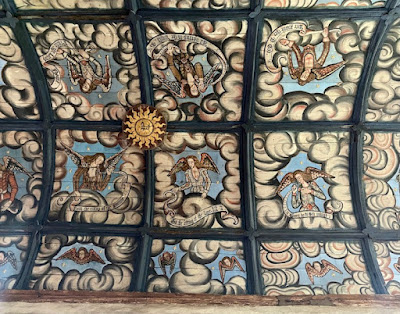

En route across Somerset, I decided to stop at Muchelney, where I’d not been for years. I planned to revisit the medieval abbey, but was also drawn to the adjacent but quite separate parish church of Saints Peter and Paul. The church is late-15th century, like so many in Somerset, but what I most wanted to see again was a later embellishment, the 17th-century ribbed and boarded ceiling of the nave, with its wonderful painted panels of angels looking down from the clouds.

I have not seen anything else quite like this ceiling (the angels in the church ceiling at Bromfield, Shropshire, come closest, but I’d say they are slightly later and in a different style). Each panel at Mucheleny is edged with clouds, which swirl like cotton wool or whipped cream, but are edged in darker shades. English clouds, of course, often combine the hopeful white with the threatening grey, but not quite in the stylized way of these ceiling paintings, and the stylization is part of their charm, which is easier to appreciate if you click on the image to enlarge it.

I find the angels charming too. They stand behind the clouds, and look down through the gaps between them; behind each figure is blue sky dotted with tiny stars, suggesting the angels are in a heavenly realm far above the clouds, farther still from us earthbound humans. They’re a far cry from medieval angels of any kind; neither are they like chaste Victorian angels. They have boldly painted faces, shoulder-length hair, and perky wings and they are are clothed in something like Elizabethan or Jacobean dresses, but in what Pevsner describes as ‘extreme décolletage’. The contours of their breasts vary – some look markedly rounded and suggest the human female form, some are less so. Those who feel compelled to explain such things suggest that their revealing costumes suggest their innocence, which sounds like a modern explainer trying very hard to justify what they see as inappropriate. Authorities such as Pevsner and the people who wrote the listing description for the church, avoid explanation altogether. I’d say anything that purports to be an explanation is at best informed guesswork.

The messages spoken by the angels, written on scrolls that they hold, are clear enough. ‘Good will towards men’, ‘Wee praise thee O God’, ‘All nations in the world…praise the Lords Name’, and so on. The sun, a golden roundel set at the intersection of four panels, looks on approvingly. From the floor below, I look up with similar approval at the whole ceiling – with more than approval indeed and with pleasure at another example of how the art of English churches can be colourful, unexpected, and full of joy.

En route across Somerset, I decided to stop at Muchelney, where I’d not been for years. I planned to revisit the medieval abbey, but was also drawn to the adjacent but quite separate parish church of Saints Peter and Paul. The church is late-15th century, like so many in Somerset, but what I most wanted to see again was a later embellishment, the 17th-century ribbed and boarded ceiling of the nave, with its wonderful painted panels of angels looking down from the clouds.

I have not seen anything else quite like this ceiling (the angels in the church ceiling at Bromfield, Shropshire, come closest, but I’d say they are slightly later and in a different style). Each panel at Mucheleny is edged with clouds, which swirl like cotton wool or whipped cream, but are edged in darker shades. English clouds, of course, often combine the hopeful white with the threatening grey, but not quite in the stylized way of these ceiling paintings, and the stylization is part of their charm, which is easier to appreciate if you click on the image to enlarge it.

I find the angels charming too. They stand behind the clouds, and look down through the gaps between them; behind each figure is blue sky dotted with tiny stars, suggesting the angels are in a heavenly realm far above the clouds, farther still from us earthbound humans. They’re a far cry from medieval angels of any kind; neither are they like chaste Victorian angels. They have boldly painted faces, shoulder-length hair, and perky wings and they are are clothed in something like Elizabethan or Jacobean dresses, but in what Pevsner describes as ‘extreme décolletage’. The contours of their breasts vary – some look markedly rounded and suggest the human female form, some are less so. Those who feel compelled to explain such things suggest that their revealing costumes suggest their innocence, which sounds like a modern explainer trying very hard to justify what they see as inappropriate. Authorities such as Pevsner and the people who wrote the listing description for the church, avoid explanation altogether. I’d say anything that purports to be an explanation is at best informed guesswork.

The messages spoken by the angels, written on scrolls that they hold, are clear enough. ‘Good will towards men’, ‘Wee praise thee O God’, ‘All nations in the world…praise the Lords Name’, and so on. The sun, a golden roundel set at the intersection of four panels, looks on approvingly. From the floor below, I look up with similar approval at the whole ceiling – with more than approval indeed and with pleasure at another example of how the art of English churches can be colourful, unexpected, and full of joy.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)