Thursday, July 30, 2015

Nottingham

Energy and eclecticism

I’ve just finished teaching a course on Victorian architecture, so thought I’d share a Victorian building or two in the next couple of posts – perhaps one or two that I’ve seen recently but did not find space for in the course. Today’s example is a building from the centre of Nottingham. In my course I talked briefly about the vast, very red brick Prudential Building in London’s Holborn, designed by Alfred Waterhouse. Here’s another example of this architect’s work for the insurance company, this time in the centre of Nottingham.

Nottingham’s former Prudential building stands in the centre of the city, on a tight corner looking towards the market place. Waterhouse used the corner to take the building through a dramatic curve, with the entrance at the centre of this curve, and as you look up, you see an array of pilasters and statues (all in terracotta), rising to a square tower that has turrets at the corners and a chunky spire. Like the London Prudential building, it’s very red, but it stands on a very heavy-looking stone base. This base seems to speak a language of solidity and security that’s echoed by the turrets and tower – appropriate, perhaps for an insurance company. Another ‘security’ feature is provided by the false machicolations – the row of little arches above the doorway that are meant to recall similar openings on the gatehouses of castles, through which defenders could pour boiling oil (or boiling water, or whatever else they could find) on their enemies below.

Yet this very eclectic 1890s building* also looks quite palatial, with its big windows and curvy Jacobean-style gables and its rich decoration, This was also conceived as the office of an institution that wanted to suggest

financial security as well as physical security. Waterhouse clearly knew what his client wanted – he designed Prudential office buildings in London, Leeds, Sheffield, and in around 20 other locations. His vivid red brick work for the insurance company reflected the Victorians’ restless eclecticism, but also their unstoppable energy.

- - -

*There’s a date on the front, 1848, but this refers to the foundation of the company, not the construction of the building.

Wednesday, July 22, 2015

Lechlade, Gloucestershire

Headgear

As in so many streets in small Cotswold towns like Lechlade – at Thames-side town in fact on the edge of the Cotswolds not far from William Morris's Kelmscott – there's an abundance of traditional vernacular limestone architecture and a sprinkling of the 'polite' architecture of the Georgian period too. So these low, limestone buildings, with the their roofs of stone 'slates' are countrified in overall appearance but have polite Georgian-style elements too: sash windows with small panes, and one door with a semicircular fanlight with glazing bars like the spokes of a wheel. Dressed stone window surrounds add to the formal effects, in keeping with the date of 1743 that appears on the sundial.

But what of the curved bay in the middle, encroaching on the pavement and surprising the passing pedestrian? It has a triangular pediment, but this has to curve to follow the line of the wall and ends up looking a bit like a bishop's mitre, taking the language of classical architecture in an unusual direction. Pevsner calls this feature a 'gazebo bay', and it certainly enables the inhabitants to look out on to the street in different directions, as those in a gazebo might do in a garden – or the occupant of a toll house might on a turnpike road. But it doesn't really look like a gazebo or a toll house. Nor does the bowed shape have quite the raffish effect of Regency bow windows in Brighton. It's a bit of Cotswold whimsy, I think, and none the worse for that.

Saturday, July 18, 2015

Amberley, Sussex

Primal light: Illustration of the month

My illustration this month comes from a book published in 1921, Highways and Byways in Sussex, written by E. V. Lucas. I’ve chosen what I think is one of the most evocative of the illustrations, a study of the church and churchyard at Amberley, by F. L. Griggs.

Etcher, illustrator, conservationist, and Arts and Crafts movement leader Frederick Landseer Maur Griggs (1876–1938) grew up in Hertfordshire, went to the Slade, and settled eventually in Chipping Campden in the Cotswolds. There he became a member of the local group of Arts and Crafts luminaries, such as the architects Norman Jewson and Ernest Gimson, and he made etchings inspired by Cotswold architecture and landscape and did illustrations for several of Macmillan's Highways and Byways books. He was an enthusiast for the work of the great 19th-century English artist Samuel Palmer, making prints of some of Palmer's etchings, and becoming, in this and in his original work, a kind of creative bridge between Palmer and the British Neo-Romantic artists of the 20th century – Piper, Sutherland, John Minton, and so on.

The illustration I've chosen from Highways and Byways in Sussex shows Griggs' mastery of atmosphere. The artist faces the evening sun, which is already quite low in the sky, and which throws much of the church and the nearby trees into shadow while also catching the roof and the side of the tower and bathing them in light. The sun also highlights the edges of the gravestones, helping to define their curved tops.

When we look more closely, it's clear that there's a huge amount of delicate detail in the illustration too. Although this is not one of Griggs' images that delineates every stone of every wall, quite a lot of masonry at the right-hand end of the church is picked out clearly, as is the metalwork of the narrow lancet window. The areas in deep shadow also have a lovely texture – Griggs was good at shadows, as another illustration I posted some time ago also shows.

More than this, the light bathing the scene works on all kinds of levels. The westerly sun's pervasive rays suggest the warmth of a summer evening – that golden hour that photographers and film-makers love. This warm light makes dramatic forms of the building and trees, encouraging us look anew at the dark shape of the left-hand tree, the ragged outline of the tree by the chancel, and above all the extraordinarily long slope of the roof. We know it won't look quite like this for long – the sun will soon be down and the sense of an ending hangs about the image. Yet it's not quite the end: we know that the sun will rise once more, illuminating the dark eastern wall, and making us look again anew.

- - -

Note The image file is at a slightly higher resolution than usual, and I hope this enables readers to see some of the detail in the picture by clicking on it. Apologies to those for whom this makes the image slow to appear on screen.

Wednesday, July 15, 2015

Liverpool

The early post

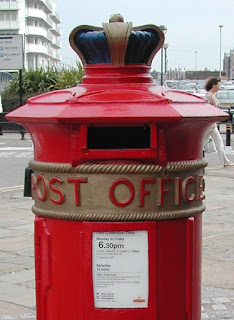

This 1863 Liverpool Special pillar box* at Liverpool's Albert Dock is the survivor of seven that were originally made for the city. It dates to a time when the idea of a standard post box (indeed the idea of a post box tout court) was still quite new. The variety of different designs made since the first boxes appeared in the early 1850s led the Post Office to introduce a standard design – a cylindrical box with a horizontal slot – in 1859. But not everyone liked it and Liverpool's authorities went for their own design. What's now called the Liverpool Special, topped with a crown, was the result.

I've posted this striking box today because the Royal Mail and Historic England† have just announced a new agreement to ensure the protection and preservation of the country's post boxes – there are 115,300 of them – in their existing locations. This comes at a time when postal services are much used (all those packages containing items bought on the internet, all that junk mail), but when the old-fashioned letter post is in decline thanks to the prevalence of email. I'm pleased this initiative is being taken: readers who return regularly to this blog with know of my liking for old boxes – pillar boxes, lamp boxes, Ludlows, and the rest. Let's all resolve to post some letters, so that they're actually used.

- - -

*The image of the Liverpool Special box is from a photograph by Steve Knight.

†Historic England is the public body that looks after England's 'historic environment'.

Saturday, July 11, 2015

Tenbury Wells, Worcestershire, and onwards

News from everywhere

July. The English summer in full if intermittent swing. England winning a Test Match against Australia. Strawberries and the occasional covenanted addition of cream. This month means many things to me, and one of them is the birthday of this blog, which began with a post about the extraordinary spa buildings in Tenbury Wells, shown in the photograph above, in July 2007.

I had no idea that English Buildings, which I began to entertain my friends, would last more than a year or two, let alone garner thousands of readers, but I'm pleased that it has done so and thankful to my readers, both those who find something to interest them en passant and the ones who have stuck it out for years. Good as it is to have readers who clearly like the buildings I post and the comments I make about them, my pleasure also comes from their comments and the way they make writing a two-way process. I have lost count of the number of things I've learned from the people who comment on my posts.

I've heard from men and women who live (or have lived) in houses that have been featured in my blog, from people who have worked or been to school in buildings that have appeared here, and so I’ve found out something about what these buildings are like to inhabit and use. Readers have shared their enthusiasms and interests too: I’ve been pointed in the direction of a gilded lion in Seaton and a wonderful black bear in Wareham. I’ve been told about old garages and petrol pumps in a variety of places. I’ve been directed towards remote churches and surprising shops and obscure public houses.

Connections too. I've joined in speculation about the links between a blue corrugated-iron garage and a coach company with a similar coloured livery. I’ve been reminded of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers films in Art Deco settings and a Michael Winner film shot in rural Herefordshire. And I got really excited when one of my pieces, reposted with additions on another blog, The Dabbler, led to a discovery. I'd shared my enthusiasm for the book Looking Round London by Helen Carstairs, and lamented that this totally unknown illustrator and writer did not seem to have produced any other books. A message came from the artist's grandson, and all was explained. Such are the revelations that the web makes possible.

These revelations are among the things I most enjoy about the internet. When they blossom into conversations, it can be especially rewarding. Among my favourite conversations (accessible in the Comments section of each post) are:

• Musings back in 2009 about the Rollright Stones in Oxfordshire that led to memories of a production of The Tempest, books inspired by the stones, the relationship between the site and county boundaries, and the depredations of tourism (in the mid-19th century the King’s Stone was said to be ‘daily diminishing in size, because people from Wales kept chipping off bits to keep the Devil off”). Not to mention the spooky feeling that many people seem to get when visiting this atmospheric ancient monument.

• A discussion in 2011 about AA roadside telephone boxes, encompassing such topics as AA badges, saluting, gardens and picket fences.

• Comments on a post (also in 2011) about a pub sign, which involved reminiscences about fireworks manufacturers, the book High Street by Eric Ravilious and J M Richards, the ban on domestic fireworks in Australia, pubs named The Antigallican, and Antonioni’s film Blow-up

• A more recent collection of thoughts, provoked by a post about some colourful cottages, on the manifold usefulness of the pig (we use ‘everything but the squeal’, people used to say), and the French chanteuse Juliette Noureddine, and her renditions of all sorts of songs, from works of Erik Satie to a song, ‘Tout est bon dans le cochon’, about pork products… ‘Only on your blog,’ as one friend put it.

My thanks to you all for reading, commenting, and sharing your enthusiasms and discoveries.

Wednesday, July 8, 2015

Saxtead Green, Suffolk

A short break

Heading out of Framlingham the other evening, it occurred to me that I'd left the café too soon after my coffee and long glass of cooling water. So when I spotted, on the A1120, a lay-by with what looked like a public lavatory, I pulled swiftly in. The lay-by was on the ‘wrong’ side of the road, but there was no other traffic and I slid across with ease.

My camera bag was on the floor of the car so, rather than put it in the boot, I slung it on my shoulder and made for the small brick building, gratefully. On emerging, I caught sight of a distant flash of white through some trees and undergrowth. A few yards of bushwhacking brought me to a fence and a view of this wonderful structure, Saxtead Green post mill, gleaming in the sunshine. The mill is said to date back to 1796, although there has been a mill here since the 13th century. It was used commercially until 1947, and is now kept by English Heritage, its white weatherboarded walls, solid roundhouse, and mostly iron machinery maintained in good order.

Having photographed the mill, I made my way back through the undergrowth to the lay-by, to be confronted by a curious bystander who'd also pulled up nearby. ‘Whatever will he think I've been doing,’ I thought, ‘lurking amongst the undergrowth near the gents?’ He eyed me for a tense moment….and said, ‘Beautiful mill, isn't it? And that's the best view of it there is.’ Some people know.

Saturday, July 4, 2015

Southwold, Suffolk

Unity in diversity

There’s a long tradition in the east of England of colour-washing houses in pastel shades. I admire this approach (and have noticed it before on a visit to Essex), finding in it a welcome contrast to the all-pervading bare stone found in my native Cotswolds, much as I like that too.* One thing that struck me in this street in Southwold is how this variety of pale colours has in fact given the row of houses visual unity. When you look at it, you don’t think ‘What a hotchpotch’ but ‘How good to see these creams, yellows, greens, and blues together, all looking of a piece’. The agreeable variations of building height, window size and chimney proportions, are all drawn together by this colour scheme. Other things unify the street, of course – the traditional pantiles on the roofs, the continuous black plinth, the almost universal sash windows. But the paint finishes on the walls do their bit too.

Another effect is that, on the green house, the colour bridges both some once-bare brick on the upper storey and a smoother plaster surface below. Not everyone likes painted brick (and some will lament that the pantiles are not accompanied by red brick walls), but not all bricks are beautiful rich reds, and the effect of the gentle ripple of the brick courses beneath a coat of pale blue or cream, as here, is rather beautiful too. Why should the beach huts of Southwold have all the colour?

- - -

*Although I did joke in my Essex post that Cotswold walls can seem a bit beige...

Wednesday, July 1, 2015

Long Melford, Suffolk

In the shade

During the recent hot days I've seen quite a few cottages swathed in roses. These in Long Melford made me pause as I made my way towards the church. I was struck by the way that the house is painted almost the same colour as the flowers so that the profuse blooms stand out more in space than in hue. Except that when you look closely, the flowers display a variety of pink shades.

Shade cast by the roses drew my eye down to the doorways below. Here what struck me were the gates fitted to each entrance, like the bottom halves of stable doors. Please bear with my ignorance: are they dog gates, to keep animals in (or out) when the main door is opened for ventilation? Or are they intended to keep small children indoors? And why not just have stable doors? Perhaps my readers can throw some light on the subject.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)