Saturday, March 28, 2015

Derby

When brick works

Just a short distance away from the ghost sign I noticed in my previous post is this building. I know a number of my regular readers appreciate a bit of brickwork, and the top of this structure seemed to fit the bill.

Now an office block, it began as Brown’s Barley Kernels Mill – barley-crushing being part of the brewing process – and was built for W. & G. Brown in the late 1880s. Although many of the more ornate Victorian industrial buildings used different colours of brick quite liberally and some are very plain, there are many that look plain at first glance but repay a second glance that allows you to take in the details. The Barley Kernels Mill is a good example. It shows only slight variations in colour – apart from the dark brick plinth and a very small amount of stone dressing, there are just a handful or two of blue bricks among the expanse of red. But up at the top of the walls, at cornice level, these bricks are handled with great vigour. The dentil course and the uppermost corbelled part with its ‘inverted triangle’ details exploit their material with economy but also, I’d say, considerable style. The brickwork seems designed to work well in good light and I was pleased I came across it when the sun was shining.

Wednesday, March 25, 2015

Derby

Morning coffee

I've watched with interest the various initiatives over the last few years to record and appreciate the ghost signs that can still be found in many towns and cities. The way they recall lost businesses and forgotten brands is one reason for my interest; their decorative qualities, whether plain or fancy, are another; the window they open on to the advertising techniques of the past is a third.

This example, fading steadily away on the gable end of a building in central Derby, is actually very plain. But even a sign like this has visual qualities one can admire – its simple lettering and the way in which some of the letters follow precisely the height of a single brick, so that the sign seems to go 'with' the brickwork rather than against it. I'm impressed that a sign-writer took such trouble – and the sign's large size must have meant that he took a considerable amount of time on it too.

The brand the sign advertises, Lever's Morning Glory Coffee, is wonderfully named but presumably long gone. I have come across a reference to the same company selling tea, but I don't know whether they were tea and coffee merchants or retail grocers. Their sign, however, with its enticing slogan, 'Tastes as good as it smells', is still worth a second look.

- - -

Some other ghost signs I've posted over the years:

Landaus and wagonettes

Beer bottlers

Dinner services, photographic film

Saturday, March 21, 2015

London, The Tower and St James's Park

The Tower, the beach, and the park: Illustrations of the Month

The phone rings. It is the Resident Wise Woman, calling me from a charity shop to ask about a book she has spotted. The line is terrible and our call is cut short, and cut short again when she calls back, but she wants to know if we have Looking Round London by Helen Carstairs. We do not. A while later she returns, clutching the most delightful children’s book I’ve seen in a long time, and one, what’s more, that I didn’t know existed. I am more and more fascinated as I turn the pages.

Looking Round London bears no date of publication, but internal evidence suggests that it came out in around 1938. It contains 22 full-page illustrations depicting the ‘sights’ of London – the great churches, the royal parks, the British Museum, the Houses of Parliament, Covent Garden market, and so on. Most of them are brightly coloured and packed with human activity – people feeding the birds, sailing in Regent’s Park, riding in Hyde Park, porters at Covent Garden and Billingsgate. There’s a lovely, free colourful line that sometimes seems to have a touch of Lowry, sometimes even of Matisse. And there’s a bit of whimsy, too, not overdone but very much there, in the form of fish-shaped clouds above Billingsgate and lines like radio waves above Broadcasting House.

My favourites among the illustrations include a lively zoo, a very red St James’s Palace, and St James’s Park, starring plants and pelicans. And the one above showing the Tower of London with children playing on the sandy beach that there used to be by the river. The figures, the colourful trees, the wavy lines in the sky and on the river are all aspects of it that catch my eye. But most of all I’m affected by what’s behind this sunny illustration – that it catches a London that, already, as the presses were rolling, had the clouds of a gathering storm approaching it, and that, in a few years more, would be blitzed.

I get the same feeling from my second example (I’m offering you two illustrations this time, because this book is so little known and apparently so scarce): St James’s Park, with Buckingham Palace in the background, pelicans at the front. The trees, bustling people, and those characterful pelicans make for an engaging image, and I especially like the details caught in a few strokes – those old-fashioned perambulators and the Royal Standard flying above the palace. It’s so moving, this sunny pre-war book, in which so many people have time for leisure and the freedom to enjoy the outdoor city. Its illustrations truly come to us from another age.

There’s another way in which this book seems distant from us. We know (or I know, at any rate) virtually nothing about its author-illustrator. Who was Helen Carstairs? Reference books and the internet tell us very little: that she was around in c 1938 and published this book. No other books seem to be credited to her. Yet she was on to something with her winning illustrations. Did she give up and do something else? Did she survive the war? Does anyone know more?

- - -

Postscript An extended version of this post appeared recently on the culture website The Dabbler. This has elicited a comment from James Leslie Carstairs, the grandson of Helen Carstairs, who confirms that Looking Round London was her only published book and fills in some more details about her life. One striking thing that emerges from this account is how much time this stylish artist of London spent overseas (in Australia, Buenos Aires, and Paris). 'Only the wanderer knows England's graces.'

Tuesday, March 17, 2015

Kidderminster, Worcestershire

Winter warmer

I and many of my readers like a good enamel advertising sign, and I’ve not yet tired of seeing old favourites such as signs advertising Palethorpe’s Sausages or Lyons’ Tea. But here’s one I’d not seen before: a cheerful red sign for the Ronoleke hot-water bottle. It takes us back in so many ways. First of all it recalls the times before central heating when British people slept in unheated bedrooms, a heap of blankets and a trusty hot-water bottle being the first lines of defence against the cold. Was that frost on the inside of the bedroom window? Yes, it was.

The sign also takes us back to a forgotten brand – forgotten by me at any rate. The unique selling point, apparently, memorialized in the name, was the leak-proof top. The Chemist and Druggist explained, in an issue dating back to October 1922:

The patent neck is a great improvement and will give satisfaction to your customers. Instead of wiring, you get a solid rubber neck built in the bottle itself. There is no washer to perish. The flange of the screw top engages with a solid rubber platform shaped in the neck. The Ronoleke is the only perfectly water tight rubber bottle and, of course, it is infinitely stronger and will outlast any ordinary make. In every way, it is a high quality production.

The Ronoleke, says The Chemist and Druggist, was backed up with a national press advertising campaign. They don’t mention enamel signs, but this survivor gives us an idea of the approach: bright colour, bold lettering, and an appeal both to those suffering from a multitude of cold-related ailments and to people who want a bottle that lasts for years and doesn’t leak. It’s a busy sign, full of words, but the red background, striped edge, and clear lettering are effective and the brand name stands out loud and clear in its outlined script.

Hats off, then, to the Severn Valley Railway, for finding this sign and putting it up at their Kidderminster station. The heritage railways do so much good work, in so many ways. As well as restoring track, rolling stock, and railway buildings, their efforts to show their stations in period style result in the preservation and display of countless bits of incidental equipment and visual detail, including many of the old signs that were once all over railway stations. Pacing the platform at Kidderminster or Bridgnorth is a real pleasure for anyone interested in the history of design and graphics, or anyone whose imagination is gripped by the social history of bed-warming or smoking or food and drink. It’s all well worth missing a train for.

- - -

Afterword Where are the hot-water bottles now? They are gone mostly, gone like counterpanes, nylon sheets, Goblin Teasmades, and other bedtime impedimenta, although teasmades, apparently are enjoying something of a revival. Anyone who fancies reading an elegy for such vanished things (digs, Ronco, Meccano, proper banks, proper doctors, Kunzle cakes, the Idea of the University), a taxonomy of loss, no less, should buy a copy of Michael Bywater's Lost Worlds: What Have We Lost, & Where Did It Go? (Granta Books, 2004). The entry on Bottles, Water, Hot is, in my opinion, worth the price of admission alone.

Saturday, March 14, 2015

Cheltenham, Gloucestershire

Colour and capitals

I was looking out for another example of the use of colour in architecture, when I came across this in one of Cheltenham’s Regency squares. The use of a pale colour (blue, grey, buff, even orange) has always struck me as effective in this kind of architecture, especially when combined with details in low relief picked out in white. The effect, especially with blue or grey walls, is reminiscent of cameo jewellery or Wedgwood pottery.

This house is a lovely example of that effect, but as I looked more closely I was even more impressed by the classical details, particularly the Ionic pilasters. The Ionic, say the textbooks and manuals of ornament, is the order with the spiral volutes in the capital. True enough, but what wonderfully spiralling volutes these are, with their rings and rings of not-quite-parallel mouldings turning towards their centres. And that’s just the start. This Ionic pilaster has much more in the way of ornament, and it's easier to make this out if you click on the picture to enlarge it. At the top, just above the volutes is the part called the abacus, here consisting of a narrow ornamental band. Looked at closely, it reveals itself to be a band of egg-and-dart ornament – yes, it’s made up of alternating ovoid and pointed shapes. Between the two spirals (the bit called the echinus) is another row of slightly larger egg-and-dart, with a narrow band of interlace just above it. And then beneath the spirals is the band known as the necking, which is adorned with a central palmette (a motif based on fan-like palm leaves), flanked by flower-like ornaments. Just beneath these, before the flute pilaster proper begins, is yet another moulded narrow band.

The ancient Greeks, and those in later centuries who copied or adapted their designs, played countless variations on these motifs. These examples are based on the capitals on the Erechtheion (below), the glorious, asymmetrical temple on the Acropolis at Athens. This is perhaps appropriate in Cheltenham, because the town’s famous caryatids – which I’ve noticed in previous posts – also derive ultimately from this temple. It’s good to see the influence working wonders once more.

Ionic capital, the Erechtheion, Athens

Photograph by Eusebius (Guillaume Piolle), used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported licence

Wednesday, March 11, 2015

Northleach, Gloucestershire

Blink and you’ll miss it

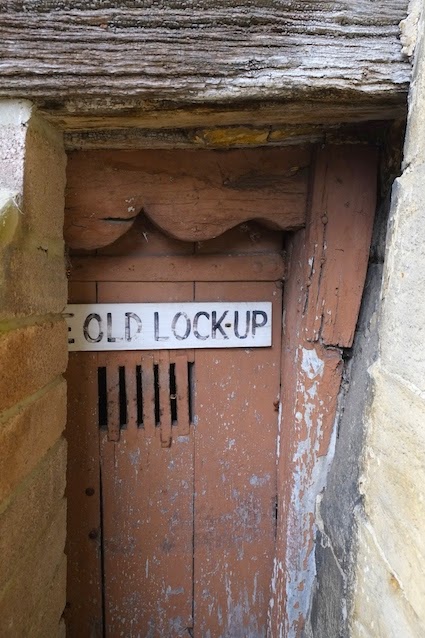

It’s easy to miss, this. Right in the centre of the small town of Northleach, in shady a corner of the Market Place in a spot shielded by other buildings, is a small brown door. The building to which is gives admittance has been propped up with an ungraceful pier of concrete blocks, so that the doorway is seriously obstructed – only about two-thirds of it is visible, and anyone of broader-than-average beam attempting to get in might have to try to enter sideways.

Tiny as this entrance is, what it is remains clear from the sign and the bars on the door. It’s the door to a town lock-up, which contains a cell about eight feet square. It’s not one of the classical free-standing lock-up structures with a stone roof that I’ve noticed before.* It’s a room adjoining the neighbouring building on the Market Place. It may be 17th or 18th century, but I could’t find out when it fell out of use. Northleach acquired a large prison, the House of Correction, just outside the town in 1789–91, but this small cell in the town centre might well have been retained after then to lock up drunks and rowdies overnight.

With its doorway partly obstructed, the cell can’t be usable for anything very much nowadays. But with its bars and its distinctive lintel, the curves of which seem to belie the utilitarian strength of the rest of the structure, it catches the eye. It would be good to think that the far-from-ideal propping could be replaced and that the building could find a use, but meanwhile one has to be grateful that a bit of history has survived.

- - - -

With thanks to Emma Bradford for pointing out this building to me.

*Other lock-ups I’ve posted about include: Wheatley, Shrewton, Breedon on the Hill, and Bisley.

Saturday, March 7, 2015

Ashby de la Zouch, Leicestershire

Geologist wanted: apply within

When I passed through Ashby de le Zouch last year it was quite late in the day. There was time only to ponder an interesting shop front, have a high-speed browse in a bookshop, and walk around the town in the gathering dusk. The impressive parish church, St Helen’s, was open, but it was virtually dark in there and I made a mental note to return; and I had to be content with jumping and stretching in front of a stone wall to try to see bits of the castle.

Looking at the outside of the church, one thing that struck me was the interesting mix of building materials. My photograph shows a section of the west wall of the tower, which is part of the original 15th-century structure. Geology is not my métier, and I’m not sure what is going on with the materials here. The red stone is fairly obviously local sandstone; the grey stone I thought must be limestone,* although there are local sandstones with a greyer or yellowish tint, so it may be one of those. There are also bits of infill in what look like reused tiles. In the first version of this post I wondered if these could be Roman tiles, but a reader (see the Comments section) quite rightly points out that they're too thin to be Roman tiles, and represent relatively modern repairs.

A bit of research, online and in books, hasn’t thrown up any clear answers to the question of the stone.§ Various sources refer to the building as a sandstone church (which it is, predominantly); one or two say “limestone and sandstone”.† If anyone knows more about the various origins of this rich and colourful array of building materials, I’d be very pleased to hear from them.

- - - -

*The Resident Wise Woman, who has been, in her time, a keen collector of fossils, also thought it looked like limestone.

§English Heritage’s informative Building Stone Atlases for Leicestershire and the neighbouring counties show mostly sandstones in this area, although there’s a patchwork of other stones in small quantities.

†Some architectural sources, such as Pevsner and the building’s official listing, barely mention materials at all. Architectural historians are often at sea when it comes to geology.

Tuesday, March 3, 2015

Evesham, Worcestershire

Emporium

Look up in Evesham High Street and you see this extraordinary bit of late-19th century facade above a modern shop front. Four very large plate-glass windows separated by columns in cast iron, surmounted by an ornate cornice emblazoned with the building’s name – Anchor House – and a balustrade, complete with urn finials and ornate decorations with palmetto leaves and scrolls that derive from ancient originals known as acroteria. As so often with the buildings I single out for comment, we’re not in the realm of great architecture here. The columns between the big windows are almost laughably slender; the lettering of the name is rather workaday; and as for the modern shopfront, I’ll restrain myself and not comment.

And yet it’s a striking frontage. It must originally have been quite an impressive shop. Quite a few late-19th century emporia had upper showrooms with big windows, letting in lots of light and even, should the objects on sale be large, the opportunity for a display that could be seen from the street. Dealers in furniture, for example, could take advantage of that kind of display, and late-Victorian department stores (which had commonly evolved from businesses such as drapers) often had lots of glass at the front, to light the deep interior and shed the best light on the goods within. Now, alas, the panes are blank and the upper floor, presumably, is given over to storage. But Anchor House still makes its mark.

Postscript

One of my readers, whose family comes from the Evesham area, notes that this building once belonged to a department store called Hamilton and Bell, which also occupied several of the adjoining buildings. This snippet of information is an example of the kind of thing that makes blogging worthwhile – I give me readers a little information and the pay me back in kind. My hunch that this could have been a department store is confirmed. I'm most grateful and have included the information here because not everyone reads the comments pages of blogs.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)