Tuesday, April 29, 2014

Bath, Somerset

Another Bath

Walking out of the centre of Bath and up Bathwick Hill, one gradually leaves behind the urban Georgian world of symmetrical crescents and terraces and comes upon another, different Bath, a Bath of asymmetry and greenery. Here, in the 1830s and 1840s, a number of large, Italianate villas were constructed, to bring a breath of the South to these otherwise very English slopes.

These houses wear their Italianate origins on their sleeve. It even begins with the names on the gate piers – Casa Bianca, La Casetta, Fiesole. These villas are essays in the Picturesque, the asymmetrical style of the early-19th century, in which towers, balconies, loggias, chimneys, and overhanging roofs are assembled to produce enticing, rather Romantic houses. Openwork balusters, and ornate chimneys add further ornate notes, although there are also typical classical details such as quoins and large keystones.

All this material was marshalled by architect Henry Edmund Goodridge to produce houses like Fiesole, the one in my photograph. Goodridge, son of a successful Bath builder, built up a large practice in Somerset and Wiltshire. He attracted prominent patrons like William Beckford, whose Lansdown Tower he designed, and this brought him numerous domestic jobs in the area, many of which show this willingness to mix Italianate and Classical styles.

This bit of Italy in Somerset is a little known aspect of Bath and embodies a different architectural approach from those we normally expect to find in the city. The Pevsner city guide to Bath finds their design ‘formulaic, heavy-handed and lacking charm’. True, the concatenation of gables and projections, the jagged roof edges and the unbalanced facades hardly add up to great architecture. But I have a bit more time for them than the Pevsner guide. I’m rather fond of this lumpy collection of varied masses. In addition, my photograph, taken on a sunny afternoon, shows the practicality of the loggias, which are providing shade (on the upper floor) and sheltered sunshine (at ground level), a combination that works as well in England as in Italy. Once the preserve of well-heeled owners, today, these facilities are available to a wider public because Fiesole is a Youth Hostel.

Flaking paint, gate pier, Fiesole, Bath

Saturday, April 26, 2014

Ross on Wye, Herefordshire

Kyrle’s green shoots, or, Odd things in churches (4)

Although one is used to seeing creepers and climbing plants of all sorts growing up the outer walls of buildings, it’s unusual to find them inside, but that’s what happens near the window at the east end of the north aisle in the parish church at Ross. These indoor creepers owe their presence to an ancient tradition.

In 1684, John Kyrle, who, known as the ‘Man of Ross’ had made numerous benefactions to his town, planted some elm trees in the churchyard. Some time later, after Kyrle had died, some shoots from one of the trees grew up through the floor of the north aisle and the parishioners, thinking it a good omen that a tree planted by the great man should be entering the church, let them be. They remained until the parent tree died and was felled in 1878.

These creepers were planted as replacements for Kyrle’s shoots and as a symbol of his good works in the town. Ross should need little reminder of their benefactor, though. Evidence of his works – a plaque in the town, his monument in the church, and enduring benefits such as the public garden known as the Prospect – survive as indications of his achievements.

Tuesday, April 22, 2014

Cheltenham, Gloucestershire

‘Peekaboo, peekaboo, here’s looking at you’

Long ago, in an era shrouded by those notorious meteorological phenomena the mists of time, I was working in the Covent Garden area of London as a publisher’s editor and the Resident Wise Woman spent her days as an arts administrator, working mainly with a group called Covent Garden Community Theatre (CGCT), which combined theatre and political comment and puppetry in a way that anticipated the more famous satire of Spitting Image, which hit the television screen soon afterwards.

Very much of their time, CGCT nevertheless found satirical targets that would not be out of place today. One of these was the prevalence of surveillance, nailed in an amusing song (we had it once, on a vinyl LP, long unplayed) called ‘Cunning B*ggers’ (I use the aposiopesic asterisk not out of mealy-mouthed prudery but due to my fear that today’s surveillance of the internet will penalize me in some way if I resort to what might be seen as obscenity). This song, of course, was about the use of listening technology. No mobile phones to tap in those days, but spies had bugs, and bugs could get anywhere: ‘We can put bugs in your clothes, We’ll put two bugs up your nose, And we cover other openings as well’, went the song. (I quote from memory, as I do in the heading to this post.)

I was reminded of all this today as I made the trip along Cheltenham’s Fairview Road to the junction with Hewlett Road, to see the new graffito, attributed to the artist known as Banksy. Here are trench-coated spies with their listening devices, and we are meant to remember that Cheltenham is home to GCHQ and that, across the other side of town, hundreds of highly trained linguists sit listening to and analysing the polyglot babble of the world’s airways – all in the interests of national security, you understand. The painting is amusing, alludes to an issue that’s rarely far from the headlines these days, and, in its positioning near a telephone box in Cheltenham, is clever and knowing. There’s also something curiously old-fashioned about it. The hats and coats, the big tape recorder and microphones – even the fact that it needs a public telephone to make its point – none of this equipment would fit up your nose, though it might get up your nose.

For many, though, the sinister side of surveillance takes a backseat in the presence of the Banksy. When I arrived at the telephone box, it was a case of joining a queue. Around twenty people were waiting to photograph themselves and their friends inside the box, surrounded by the spooks. We might resent the presence of the b*ggers, but we do not let let them get us down. The graffito has a similar demotic appeal to the 1970s work of CGCT. So form an orderly queue, and watch your language.

- - -

Some further thoughts and links

The telephone box, by the way, is a KX100 kiosk, a type created by DCA Design and introduced in 1985. It was part of a modernizing move that came soon after British Telecom was privatized. Designed to be easy and inexpensive to clean and maintain, these glass, aluminium and steel boxes were installed widely but were never as popular as the older red boxes, perhaps because they're meant to blend transparently into the background rather than asserting themselves as the much loved red phone boxes do.

Graffiti is, of course, controversial and illegal. In some cases, however, local communities embrace particular graffiti – because these actually enhance their setting or because people approve of the work or the sentiments it embodies. This particular example has already attracted defacement, swiftly followed by rescue by locals. There’s a news story about this here.

Another story highlights the hope that the Bansky will put Cheltenham ‘on the world culture map’.

And finally, for now, another report details a local plan to protect the work with perspex.

Saturday, April 19, 2014

Bath, Somerset

From the sun to the stars

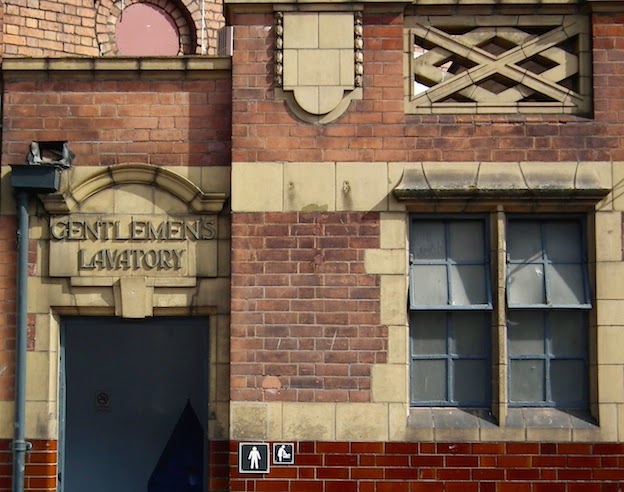

My journey to Bath, which I interrupted to visit the Bristol public lavatory in the previous post, encompassed another pissoir, this one looking sadly dilapidated, although the scars are probably mainly superficial. The building hangs on, locked up and unkempt, in a shady corner of Sydney Gardens, the park behind the Holburne Museum.

This example, like the Bristol one, is made of iron. Apparently it’s a product of the Star Works in Birmingham (the Bristol example came from the Sun Foundry in Glasgow – clearly these Victorian businesses looked to the heavens for their onomastic inspiration). The Star Works produced many such conveniences, although very few now stand. Rectilinear where the Bristol gents is rounded, it has openwork ventilation panels around the tops of the walls and rectangular panels below, each decorated with an abstract design that recalls, without reproducing exactly, a compass rose. This kind of decoration, which leaves behind the curvaceous lines of Art Nouveau, suggests a date somewhere in the second decade of the 20th century. At some stage after this, the pissoir was painted a tasteful grey, although the peeling paintwork on the side in my photograph reveals early green coats beneath – green being the most common colour for such buildings, especially when sited, as here, in public parks.

Sydney Gardens now has new public lavatories in a nearby stone-clad structure that looks very substantial. I don’t know what the future is for the Victorian building, but I hope, in preservation-conscious Bath, that it has some hope of survival.

Wednesday, April 16, 2014

Bristol

A gentlemen’s to relish

My route to Bath the other day took me around the edge of Bristol. Emboldened by my recent post of an ornate lavatory in Worcester, I decided to seek out an even more interesting example: the late-19th-century gents in the corner of Mina Road Park, in the northern part of Bristol.

The building was made, probably in the 1880s, at the Sun Foundry in Glasgow, a business founded by George Smith in the late 1850s. The Sun Foundry became prolific producers of architectural ironwork, together with such items as drinking fountains and bandstands. They described themselves as ‘Art Metal Workers, Iron Founders and Sanitary Engineers’, so they were clearly well suited to the manufacture of structures like this iron pissoir. They certainly lavished as much attention on its details as they did on projects like ornamental fountains and cast-iron Corinthian columns.

Lovely pierced panels covered with floral ornament line the upper parts of the walls, combining ventilation with decoration. The sprays of flowers, scrollwork motif, and small round finials are similar in design to the terracotta panels on many contemporary buildings. The openwork theme continues in the dome. This is a delicate and intricate network of flowers, leaves, and arabesques.

This tiny gents, practical and elegant, is an asset in the corner of the park, and it was good to see that it has been carefully maintained and painted. It’s not so good inside – the graffiti vandals have been at work – but the view up into the openwork dome, with the resulting view of the sky and breath of fresh air, is uplifting. As in Worcester, this amenity proves that a visit to the lavatory can be interesting, architecturally. It’s a pity the burghers of Bristol did not supply something similar for the ladies.

Sunday, April 13, 2014

Huish Episcopi, Somerset

Foiled again

The quatrefoil. A shape in the form of a simple stylized four-leaf clover, flattened. It’s everywhere: Gothic churches, public buildings, doorways, fabric patterns. It appears over hundreds of years, in many different cultures, in diverse contexts. It can be part of window tracery, a frame for a sculpture, a decorative motif on a wall. It’s on modern jewellery and on Louis Vuitton bags too.

It’s often made out of stone, but it’s harder to carve than a simple square or a circle or a diamond. So it’s most often used on highly ornate, high status buildings. It probably originated in Islamic art but it’s most familiar in Gothic tracery and ornament. So you’ll find it on the great French cathedrals, and on the Doge’s Palace in Venice. And on English medieval churches and Gothic revival buildings of all kinds. One of the first blog posts I ever did was about a 19th-century building in Manchester that’s in the Venetian Gothic style and has quatrefoils all over it. Now here’s an example from a medieval church at Huish Episcopi, Somerset.

My photograph shows quatrefoils used as a decorative motif on the tower of the church. I could no doubt have chosen other towers in this region of stunning towers that use this pattern, but Huish Episcopi is one of the most ornate and beautiful of all the great Somerset church towers and quatrefoils are used lavishly on it – in the horizontals bands that mark the storeys, in a vertical arrangement in the window-like openings that allow the sound of the bells to carry, in the glorious ornate openwork parapet right at the top.

One key reason why the quatrefoil succeeds as a design motif is that it manages to combine the idea of a natural form (it looks like leaves or a flower) with a very precise, reproducible geometry. In other words it’s an abstract pattern that makes us think of nature. In Gothic, the geometry of such patterns is ramified, so that there can be shapes with many different numbers of ‘foils’: trefoils with three lobes, cinquefoils with five, sexfoils with six, and so on. Medieval Christian master masons no doubt saw symbolism in these numbers. If trefoils suggest the Holy Trinity, quatrefoils perhaps remind us of the four Evangelists.

A carver at Huish Episcopi also had another idea: that the quatrefoil could accommodate the shape of Christ on the Cross. As so often in medieval architecture, high seriousness and visual facility are united.

- - -

There’s more about the quatrefoil in an episode of the marvellous 99% Invisible, the tiny but constantly entertaining and informative radio show about design. Presenter-producers Roman Mars and Avery Trufelman discuss the quatrefoil here.

Thursday, April 10, 2014

Preston Capes, Northamptonshire

Projection

It’s an experience that nearly every church crawler must know. You’re standing in a quiet country church on a dull day. Many of the windows have clear glass, with a smattering of stained glass, so the interior is not dark, but it’s not exactly bright either. Soft shadows brush whitewashed walls. Then outside the wind blows, the clouds part, and out comes the sun. Suddenly, inside, everything lights up and here and there patterns of stained glass are projected on to the stone-flagged floors and the white walls.

The moment can be magical, and when it happened to me at Preston Capes the other week the effect was so right it might have been stage managed. The yellows and blues of the glass fell beautifully on the white wall, the adjacent font, and the font cover. Not only that: the design of the glass made the outline of the two window openings clear on the wall, and their shape – tall, narrow, and with cusps pinching the top into a a tiny tear shape – roughly matched that of the tracery panels on the side of the font that was facing me.

The design of the tracery that decorates the font suggests that it’s 15th-century (the spire-shaped font cover may well be later). The font is a nice example of the late-medieval tendency to decorate architectural surfaces of all kinds with the sort of tracery patterns used in windows.* The stonework of the window might be of a similar date to the font (I didn’t check while I was there) but the glass is certainly post-medieval and not the sort of stuff one would spend much time admiring, were it not for this projection effect, that lasted for just a few minutes, before the wind blew clouds over the sun once more.

- - -

* It’s also an example of a later tendency to cover stone surfaces with stone-coloured paint, but we’ll let that pass.

Sunday, April 6, 2014

Worcester

Best foot forward

Last week I gave a talk about the history of shops and shopping, an occasion made especially enjoyable for me because of the variety of questions and anecdotes from audience members afterwards. Several stick in my mind but one of the most memorable was from a man who, now retired, had started his working life in a shoe shop many moons ago. He recalled that the crucial thing was to get everyone entering the shop to sit down and remove their shoes. The assistant could then helpfully bring many pairs of shows for the customer to try on, while the customer, parted from his or her own footwear, was effectively glued to the spot. In this position it was almost impossible for them to escape without buying a pair of shoes – as well as the polish, polishing cloth, shoe horn, or whatever else the enterprising assistant could persuade them that they needed.

A lot of my talk had to do with the way the design of shop fronts attracted the customer, but I didn’t discuss the old-fashioned symbolic shop signs that were widely used until the early-20th century. These signs are not so common now. You’re more likely to find them in a museum than on the High Street, but my photograph shows one still hanging above a shoe shop in Worcester. The golden boot was once a popular sign for a shoe- and boot-maker and golden boots also survive in Launcesron and Maidstone, amongst other places. Others in the trade used a shoe, patten, or slipper, often together with a crown, and cobblers sometimes had a painting of St Crispian, their patron saint. Allied trades, such as saddlers, leatherworkers, and breeches-makers had their own signs – a saddle or horse, for example, or a pair of leather breeches.

A beautiful golden boot like this certainly helped make a shoe-maker’s shop visible and distinctive, and was of course very effective in an era when many potential customers could not read or write. Now that few shops have such signs, and most retailers try to stand out with a more or less well designed two-dimensional sign, the old-fashioned 3D sign once again helps its owner stand out from the crowd.

Wednesday, April 2, 2014

Worcester

Well spent

Small things matter. A gents in a city centre, for example. Designed with some care, as if to suggest pride in a civic amenity, rather than shame at bodily functions. Somebody in Worcester made an effort.

So what have we got? A winning mixture of the showy and the practical. Glazed bricks cover the lower portion of the wall (just visible in the photograph above) with a careful curve at the doorway, as if to be kind to stumble-bums who make contact with the masonry while entering in haste. A mixture of red bricks and buff dressings, with their suggestion of richness, articulate the upper area of the wall. Mullioned windows and a decorated parapet are testimony to that blend of influences often found in buildings of the years on either side of 1900. Above the doorway, there’s another mixture – a keystone topped, and trumped, by lettering in a raised panel headed with a curving moulding. The lettering is big, but not too big, ornate, but not too fancy – the curved side of the A and the generous loop of the R seeming to give a hint of a memory of Art Nouveau. Civic pride is reinforced by the coat of arms further along the wall, in its panel that sets it off from the parapet and raises it slightly above.

Modernity, in the shape of a poorly positioned down pipe and hopper head and two little square signs, intrudes, but not too much. This small building is still an ornament to the street. Worcester’s pennies were not so badly spent.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)